In 2011 an American educational consultant working in Kathmandu, Nepal, was flummoxed by the rote teaching she saw in her schools classroom with children mindlessly copying down lectures and by the lack of resources to get beyond it. The school was too poor to buy anything.

So she had the kids go to a nearby river where they collected stones of every shape, size and color. They collected two barrels of stones back at the school, where children were told to grab as many stones as they liked and just build something.

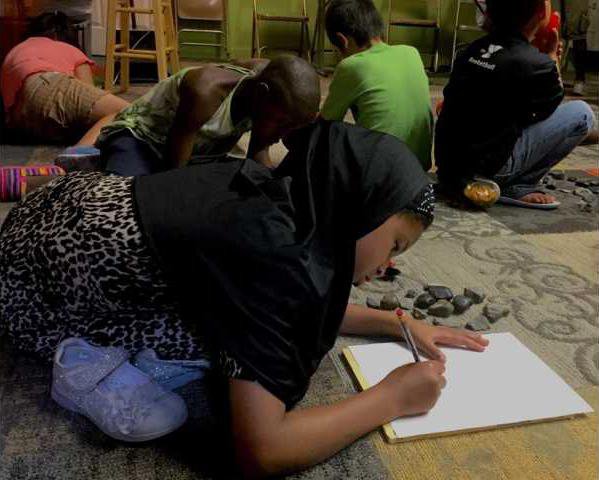

The video from that first day in Nepal shows remarkable energy and enthusiasm combined with meditative mindfulness. Kids buzz around scooping up stones, sorting through them, and arranging them into everything from helicopters and lizards to flowers and birthday cakes some with the proverbial tongue of concentration pursed between their lips, others chattering to their neighbors and borrowing stones.

Upon returning to the U.S. later that year, Massachusetts-based retired education professor Diana Suskind honed her program into Stonework Play, seeding it from coast to coast, while developing it further in Asia and exporting it to the UK.

Stones are a kinesthetic medium, never fixed in their place or meaning, the ground an endless canvas, Suskind says, and small hands are the brushes.

At a time when education is increasingly focused on testable skills, policy-makers worry that kindergartners are not "prepared," and everyone is discussing preschool curriculum, many creativity experts worry about the rush to measurable outcomes and see promise in the radically simple open-ended creativity exercise Suskind developed in Nepal.

Until recently, in Western countries everyone grew up this way, says Peter Gray, a psychology professor at Boston College. Kids learned mostly in free, un-directed play. Unfortunately, developing nations have copied the worst of the Western model.

Stretching the mind

Teachers today struggle to balance the pressure of structured curriculum with free-flowing activities that stretch the mind, said Dr. Rosa Aurora Chavez, a psychiatrist who directs the Washington International Center for Creativity in Washington, D.C. She thinks stonework could help counter overpowering force of formal demands.

The children are transforming the stones," Chavez said, "but they dont suggest anything. They are very neutral. Other natural objects could be used similarly, like leaves or sticks. But the stones have a beauty of their own.

One of Stonework's many avid fans is Gail Nadal, Director of Early Childhood Education at the Yolo County Office of Education in Northern California.

Stonework is about time for children to be creative using natural resources, Nadal said. Children just need time, time to explore and raw materials to play. You dont need a grant or anything. You just need some baskets of stones.

Nadal said her Head Start programs use stones extensively in the classroom, allowing young children to practice sorting shapes and colors and sizes, key early development skills. They also put baskets by the mats during nap time, so kids who arent sleeping can engage in restful, creative play. They even have boxes of large rocks in the playground, which kids cart around in wagons.

Symbolic discovery

Suskinds stonework epiphany actually began with a pineapple. A teacher at the Katmandu school asked the children to draw the fruit, holding up a picture of a pineapple. But the children had never seen, let alone tasted one.

I ran to the local store and bought a pineapple, Suskind said. I let them guess how it would taste. Sweet or sour? I had them hold it, feel it and taste it. Then they drew it, incorporating it into lesson.

Later, Suskind bought each child a pair of scissors. They had never held scissors before and were fascinated with it and what it can do. After the scissors, I then looked on the ground and saw a moveable natural object stones.

The truth is it was free, and I was tired of using up my money, Suskind admits.

Despite its spontaneous and rough-hewn origin, Suskind quickly formed a vision for how she wanted the method to work. The creations would be open-ended and spontaneous, but the children would be asked to give their work a title, tell stories about it and draw a picture. Then the students walk around the resulting gallery and share their stories.

The storytelling element has been an important and an enduring facet of the program. Thats when the stories come to life for the children, Gail Nadal said, noting that in Yolo County the children make storybooks of their stone play, combining photos and drawings and narratives.

For very young children, this link between natural objects and storytelling could be valuable step toward symbolic thinking, Rosa Chavez suggests. There is a key transition when objects come to stand as symbols in a childs mind, Chavez said. They come to represent something other than themselves, as bridges between the concrete and the abstract.

Structured freedom

There is, Suskind says, nothing contradictory in having a structure within which the free play and discovery take place. Almost everything is learned, she says, and creativity is not necessarily spontaneous. It's learned and facilitated and encouraged.

Suskinds stone system strikes a balance between form and freedom, Peter Gray said. He compares Stonework Play to the current popularity of adult coloring books, which are relaxing and creative, but also very preformed. The stones are much more free form and are, of course, natural materials, but there is a similar meditative quality.

Play always has structure, Gray argues. Its hard to be creative absolutely from scratch. The other extreme, Gray says, would be to send kids out into a forest and say, Be creative. The stones, Gray says, strike that balance between freedom and form.

Mark Runco, a cognitive psychologist and professor of Creativity Studies at the University of Georgia, agrees. He calls this optimal constraint and a realistic view of creativity.

Creativity rubric

Runco is a widely respected creativity expert who has done significant consulting for Lego, and he's just issued "Assessing Student Creativity," a guide for parents and teachers to measure various facets of creativity.

Its easy to see how Suskinds stone method fits right in to Runcos creativity rubric, which includes headings such as self-expression, problem solving and flexible thinking. Creative students will also build something different from others and consider a number of options, to name a just a few of the boxes.

I really liked what I saw, Runco said of the Stonework Play model, which he had not previously encountered.

Runco notes certain similarities between the stonework and the admittedly more costly Lego approach. Legos have the advantage of being able to build more easily into three dimensions, he said, but the stones counter that with by encouraging naturalistic creativity with natural objects.

Also, the stones are free.

Unintended discovery

I think the approach has a lot going for it as an art medium, says James Catterall, director of the Centers for Research on Creativity and an emeritus education professor at UCLA.

Part of what attracts Catterall is the natural materials. Theres an attachment to the environment to where the pieces come from, an aroma, a connection to the land, he said.

He also sees the stones as non-threatening. If you are working with water colors there are certain skills you need to render anything effectively," Catterall said, but the stones are not intimidating at all. You can rearrange them and keep going.

But one of Catteralls most intriguing insights is Stoneworks potential for serendipity. There is something magical, he suggests, in thinking about the materials, concentrating, grouping the shapes and colors, and then doing something one didnt set out to do but nonetheless achieves something both was unintended and pleasing.

Achieving something you did not intend to do is more likely with stones than with crayons, Catterall notes. When you start with a box of crayons, he said, you are bound to paint a tree, a wagon, or a horse. But the stones are more open-ended and can be constantly rearranged without leaving a mark."

More research

Chavez thinks Stonework Play lends itself further research. Qualitative researchers could observe student behavior during exercises, using metrics of key creative processes, she suggested. And quantitative research could measure feelings of well-being or problem solving skills after working with the system.

Such research might help refine the system and suggest usages and implications for different stages and different challenges. It might also point to tweaks that could improve the approach.

For her part, Suskind is open to suggestions, but not too hung up on scientific proof. The proof is in the creative pudding, she says. Even children who routinely learn by simple memorization have an incipient creativity that can blossom if encouraged. That's what Stonework Play is all about.

So she had the kids go to a nearby river where they collected stones of every shape, size and color. They collected two barrels of stones back at the school, where children were told to grab as many stones as they liked and just build something.

The video from that first day in Nepal shows remarkable energy and enthusiasm combined with meditative mindfulness. Kids buzz around scooping up stones, sorting through them, and arranging them into everything from helicopters and lizards to flowers and birthday cakes some with the proverbial tongue of concentration pursed between their lips, others chattering to their neighbors and borrowing stones.

Upon returning to the U.S. later that year, Massachusetts-based retired education professor Diana Suskind honed her program into Stonework Play, seeding it from coast to coast, while developing it further in Asia and exporting it to the UK.

Stones are a kinesthetic medium, never fixed in their place or meaning, the ground an endless canvas, Suskind says, and small hands are the brushes.

At a time when education is increasingly focused on testable skills, policy-makers worry that kindergartners are not "prepared," and everyone is discussing preschool curriculum, many creativity experts worry about the rush to measurable outcomes and see promise in the radically simple open-ended creativity exercise Suskind developed in Nepal.

Until recently, in Western countries everyone grew up this way, says Peter Gray, a psychology professor at Boston College. Kids learned mostly in free, un-directed play. Unfortunately, developing nations have copied the worst of the Western model.

Stretching the mind

Teachers today struggle to balance the pressure of structured curriculum with free-flowing activities that stretch the mind, said Dr. Rosa Aurora Chavez, a psychiatrist who directs the Washington International Center for Creativity in Washington, D.C. She thinks stonework could help counter overpowering force of formal demands.

The children are transforming the stones," Chavez said, "but they dont suggest anything. They are very neutral. Other natural objects could be used similarly, like leaves or sticks. But the stones have a beauty of their own.

One of Stonework's many avid fans is Gail Nadal, Director of Early Childhood Education at the Yolo County Office of Education in Northern California.

Stonework is about time for children to be creative using natural resources, Nadal said. Children just need time, time to explore and raw materials to play. You dont need a grant or anything. You just need some baskets of stones.

Nadal said her Head Start programs use stones extensively in the classroom, allowing young children to practice sorting shapes and colors and sizes, key early development skills. They also put baskets by the mats during nap time, so kids who arent sleeping can engage in restful, creative play. They even have boxes of large rocks in the playground, which kids cart around in wagons.

Symbolic discovery

Suskinds stonework epiphany actually began with a pineapple. A teacher at the Katmandu school asked the children to draw the fruit, holding up a picture of a pineapple. But the children had never seen, let alone tasted one.

I ran to the local store and bought a pineapple, Suskind said. I let them guess how it would taste. Sweet or sour? I had them hold it, feel it and taste it. Then they drew it, incorporating it into lesson.

Later, Suskind bought each child a pair of scissors. They had never held scissors before and were fascinated with it and what it can do. After the scissors, I then looked on the ground and saw a moveable natural object stones.

The truth is it was free, and I was tired of using up my money, Suskind admits.

Despite its spontaneous and rough-hewn origin, Suskind quickly formed a vision for how she wanted the method to work. The creations would be open-ended and spontaneous, but the children would be asked to give their work a title, tell stories about it and draw a picture. Then the students walk around the resulting gallery and share their stories.

The storytelling element has been an important and an enduring facet of the program. Thats when the stories come to life for the children, Gail Nadal said, noting that in Yolo County the children make storybooks of their stone play, combining photos and drawings and narratives.

For very young children, this link between natural objects and storytelling could be valuable step toward symbolic thinking, Rosa Chavez suggests. There is a key transition when objects come to stand as symbols in a childs mind, Chavez said. They come to represent something other than themselves, as bridges between the concrete and the abstract.

Structured freedom

There is, Suskind says, nothing contradictory in having a structure within which the free play and discovery take place. Almost everything is learned, she says, and creativity is not necessarily spontaneous. It's learned and facilitated and encouraged.

Suskinds stone system strikes a balance between form and freedom, Peter Gray said. He compares Stonework Play to the current popularity of adult coloring books, which are relaxing and creative, but also very preformed. The stones are much more free form and are, of course, natural materials, but there is a similar meditative quality.

Play always has structure, Gray argues. Its hard to be creative absolutely from scratch. The other extreme, Gray says, would be to send kids out into a forest and say, Be creative. The stones, Gray says, strike that balance between freedom and form.

Mark Runco, a cognitive psychologist and professor of Creativity Studies at the University of Georgia, agrees. He calls this optimal constraint and a realistic view of creativity.

Creativity rubric

Runco is a widely respected creativity expert who has done significant consulting for Lego, and he's just issued "Assessing Student Creativity," a guide for parents and teachers to measure various facets of creativity.

Its easy to see how Suskinds stone method fits right in to Runcos creativity rubric, which includes headings such as self-expression, problem solving and flexible thinking. Creative students will also build something different from others and consider a number of options, to name a just a few of the boxes.

I really liked what I saw, Runco said of the Stonework Play model, which he had not previously encountered.

Runco notes certain similarities between the stonework and the admittedly more costly Lego approach. Legos have the advantage of being able to build more easily into three dimensions, he said, but the stones counter that with by encouraging naturalistic creativity with natural objects.

Also, the stones are free.

Unintended discovery

I think the approach has a lot going for it as an art medium, says James Catterall, director of the Centers for Research on Creativity and an emeritus education professor at UCLA.

Part of what attracts Catterall is the natural materials. Theres an attachment to the environment to where the pieces come from, an aroma, a connection to the land, he said.

He also sees the stones as non-threatening. If you are working with water colors there are certain skills you need to render anything effectively," Catterall said, but the stones are not intimidating at all. You can rearrange them and keep going.

But one of Catteralls most intriguing insights is Stoneworks potential for serendipity. There is something magical, he suggests, in thinking about the materials, concentrating, grouping the shapes and colors, and then doing something one didnt set out to do but nonetheless achieves something both was unintended and pleasing.

Achieving something you did not intend to do is more likely with stones than with crayons, Catterall notes. When you start with a box of crayons, he said, you are bound to paint a tree, a wagon, or a horse. But the stones are more open-ended and can be constantly rearranged without leaving a mark."

More research

Chavez thinks Stonework Play lends itself further research. Qualitative researchers could observe student behavior during exercises, using metrics of key creative processes, she suggested. And quantitative research could measure feelings of well-being or problem solving skills after working with the system.

Such research might help refine the system and suggest usages and implications for different stages and different challenges. It might also point to tweaks that could improve the approach.

For her part, Suskind is open to suggestions, but not too hung up on scientific proof. The proof is in the creative pudding, she says. Even children who routinely learn by simple memorization have an incipient creativity that can blossom if encouraged. That's what Stonework Play is all about.