The average American family's financial picture may be flat or even flailing, set against a backdrop of little lucrative work for men who didn't go to college and an income gap between the richest and everyone else that is widening. But for all the headlines and hand wringing, not much has been said about how marriage could stabilize families.

Economic wellbeing and family structure are connected, according to a report released Tuesday by the American Enterprise Institute and the Institute for Family Studies. The report was the subject of a pair of panel discussions hosted by AEI in Washington, D.C.

The effect marriage has on families financially is on the order of the impact a college degree has compared to dropping out of high school, said Robert I. Lerman, co-author of "For Richer, For Poorer: How Family Structures Economic Success in America."

"Only rarely do we see a mention of this key factor of the changing structure of American families," Lerman said. "Rarely, relative to its importance."

He and co-author W. Bradford Wilcox said children who grow up with both parents are more likely to follow a "success sequence" of graduating from high school, going to college or work, and getting married before the first baby's born. That order is most likely to yield economic and other wellbeing, they wrote.

Lerman is a professor of economics at American University and a fellow at the Urban Institute, among other titles, while Wilcox's titles include director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia and fellow/scholar at both institutes.

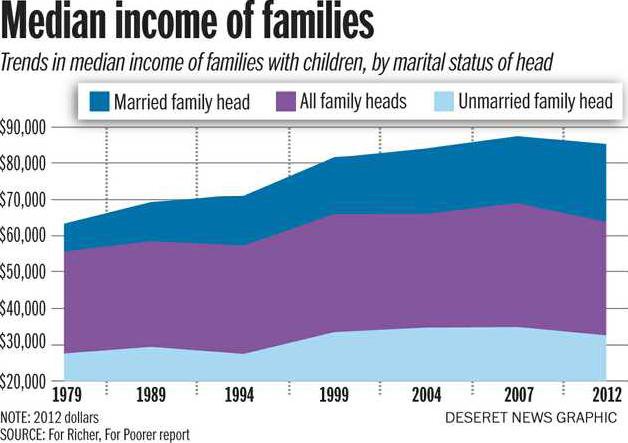

Lerman and Wilcox said married couples who were themselves raised in intact families enjoy a family income "premium" of at least $42,000 compared to unmarried peers raised in non-intact families. While the amount varies, benefits are there regardless of race.

Some suggestions

Wilcox believes the growing marriage divide between the college-educated and others erodes the American dream and is tied to stagnating families, income inequality, unemployment and lower economic mobility for poor kids. "Marriage seems to transform men," he said. "They work longer hours, they work more strategically, they earn more money."

Lerman and Wilcox highlight public policies to encourage marriage, calling for changes so low-income couples don't fear that marriage would end their ability to receive public assistance benefits. They support raising the child credit to $3,000 and expanding the maximum earned income tax credit for childless single adults to $1,000.

They also cite a need to improve vocational education or apprenticeships for those who are not building careers and economic futures on the foundation of having gone to college. Finally, they said public schools, government and businesses should encourage young adults to follow the so-called success sequence.

To point out why those things are important, the duo presented the hypothetical case of "Jane," raised in an intact family. At 30, according to their research, she's working about 179 more hours a year than friends raised by single parents and she earns about $4,700 more. Statistically, she's 9 percent more likely to have graduated high school or gotten a GED, 12 percent more apt to be married, and 12 percent less likely to have had a baby before she wed.

Joe, a boy who grows up with his married parents, at age 30 works an average of 156 more hours a year than his single peers and earns about $6,500 more. He is 15 percent more likely to have a diploma or GED, 10 percent more likely to be married, and 5 percent less likely to become a non-custodial parent, they said.

"The shifting sands of our economy have proved to be much more treacherous for less-educated men," Wilcox said.

Family structure, he and Lerman note, is "about as good a predictor of personal and family income for young men as race/ethnicity and a stronger predictor of income than whether their mother is college educated."

As for women, while education and ethnicity strongly predict individual income, marriage better predicts family income.

Many views

Scholars and commenters from different backgrounds and political persuasions each commented on the report during the panels.

"It's remarkable" a discussion of family "gets pushed to the edges" when talking about the economy, said panelist Elisabeth Jacobs of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. "Economic context can set people up for successful family formation."

But she noted that family formation and economics have gone in opposite directions, creating rising inequality, although couples make decisions based on what they see as their economic prospects.

Women expect more from a potential husband at the same time that men who are not highly educated find it increasingly hard to make enough to support families, making marriage less appealing. Jacobs said low-income women consistently tell researchers instability and potential for divorce make getting married less appealing.

"These ladies aren't crazy," she said. "... It's very difficult to have a stable marriage if your economic life is very unstable."

Isabel Sawhill, with Brookings Institution Center on Children and Families and author of Generation Unbound, commended the report for trying to answer suggestions that associations between marriage and family stability actually arise because people who marry have different characteristics than those who don't. But she wondered if the authors considered differences created because so many women now work. "Are we assuming this is what it would look like if women had worked as much in the past?"

If everyone did agree "marriage does matter for all kinds of reasons and we want more of it, how would we get there?" she asked. Sawhill noted other barriers to family economic stability and said there is a need to slow the number of unplanned births.

Consensus?

Various panelists suggested a politically divided nation might still find areas of consensus when it comes to family, despite squabbles over cause and effect.

"I have a sense that both sides are trying to change the conversation away from the main priority, and there's a great lack of trust," said Slate's Jordan Weissmann. He noted a "degree of nervousness" when conservatives focus on single mothers instead of how much money the very rich have. "If you talk about single mothers, you're not talking about the rise of the .1 percent," he said, referring to the very richest Americans.

AEI's Nicholas Eberstadt suggested that exploding incarceration rates may be a barrier to family stability and yet another reason couples don't marry because incarceration and its aftermath makes it hard to find a job or a spouse.

New York Times columnist Ross Douthat and Washington Post financial columnist Michelle Singletary also discussed incarceration rates. Douthat said people on both sides of the political aisle might consider some reforms of policies created during an "era of sky-high crime rates" that have now gone down.

Singletary said she teaches finances to inmates about to be released because they will face real financial challenges, like how to find a job when they have to admit they were in jail.

As for helping families stabilize, she said she's not waiting for government, but rather is working in her own community and church to help families strengthen their finances and personal relationships. She also believes too few people rejoice in their marriages, to their detriment.

A video of the panel discussions is available online.

Email: lois@deseretnews.com, Twitter: Loisco

The marriage between economic success and family structure in America