Last week, we visited 1973, at the time the last of the United States soldiers were pulled out of Vietnam. As it turns out, Marine PFC Edward Lloyd Saenz was not the only Vietnam casualty from that war. Historian Karen Neuforth found the names of five others in the files of the Department of Defense online archives. They include Army Specialist Fourth Class Kent L. Amerine, Great Bend, who died Aug. 2, 1966 at LZ Pink, Chu Pong Massif, Pleiku Province; Air Force Col. Carl Frederick Karst, Galatia, who died Aug. 2, 1974 at Pleiku Province; Marine PFC Robert Eugene Riedel, Hoisington, who died Aug. 31, 1965 at Quang Nam Province; Army Second Lt. John Stephen Simmons, Hoisington, who died March 1, 1968 at Dinh Tuong Province; and Army Specialist Fourth Class Conrad Francis Straub, Claflin, who died Feb. 27, 1967 at Tay Ninh Province. In addition, we received notice from Mary Lou Warren that Col. Karst was missing in action after his plane was shot down, and was declared several years after the end of the war. Perhaps the list is not yet complete, and as always, we welcome further information.

Each week we’ll take a step back into the history of Great Bend through the eyes of reporters past. We’ll reacquaint you with what went into creating the Great Bend of today, and do our best to update you on what “the rest of the story” turned out to be.

While Hitler demanded “hatred and more hatred” in Berlin, Americas and others considered the advantages of a favorable exchange rate. “Cheap Living in Germany: Coblenz a rendezvous for Americans seeking low living costs,” ran in the April 7 edition of the Tribune. The story said cheap living in that area of the Rhine continued to attract Americans abroad, often coming first to visit the American occupied areas.

“How it works out for the German is another matter. What is cheap to the foreigner is dear to him,” it reads. It goes on to tell the story about a man who had good luck following the war, accumulating enough to purchase a farm for his family and produce a nice harvest. However, the devaluation of the mark halved the value of his crop and land.

“He sold most of his land is now obliged to work for a few thousand marks a day, with the mark still depreciating in value and prices going higher. He and his family now eat black bread and wear rags.”

A story in the April 4, 1923 edition of the Great Bend Tribune, “$10 like a fortune: Extreme poverty in Austria told by Dodge City man’s sister,” spoke of the relative luxury experienced by ex-pat Americans while in Germany, which was undergoing a slow and painful recovery following World War I.

“Joe Randl, a young Austrian who is employed by W.F. Rhinehart on his ranch (Dodge City) has a letter which tells a graphic story of the extreme poverty of the Austrian people,” the article begins. Randl sent his sister in Austria $10, which at the time was a very extravagant gift. “The $10 sent from this country purchased 10,000 marks in Austria...which purchased a pound of meal, a pound of lard, a pound of meat, a pound of bread, a pound of potatoes, a pound of sauerkraut, a pound of salt, a quart of milk, and a gallon of coal oil.” The family was living off what little money the father could earn in a day, which was just enough to buy food for the evening meal.

On April 13, 1923, Hitler would give a speech in Munich, Germany, proclaiming it the responsibility of Germans to avenge the deaths of those who died in World War I and rebuild Germany, pointing especially to Jews and the United States and France as the main culprits.

In November, the Nazi party leader would return to Munich where he would lead a failed coup attempt that would land him in jail. While there, he would write his memoir, “Mein Kampf.”

Delete - Merge U

However, closer to home, people continued to work. Near Lyons, an Italian worker was saved from a salt mine in which he was drowning in, much the same way has been described in recent reports of accidental deaths from walking down grain in grain bins.

“Lago had been sent to one of the elevated storage bins to shovel salt to a freight car. A slide was caused which buried lago and almost suffocated him. Had rescuers been two or three minutes later in reaching him, he probably would have been dead.”

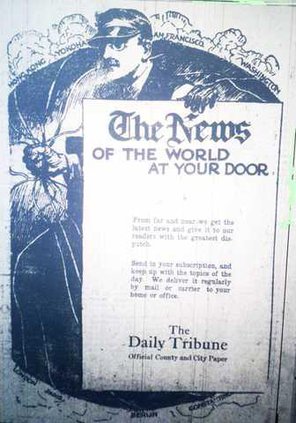

The Great Bend Tribune of the 1920’s prided itself on being the top source in the area for world news. It was a good time for the paper, so good in fact, it announced it would begin it’s building fund, and expressed its trust that its subscribers would help the cause by getting their bills paid on time.

“...the paper has outgrown its quarters. The working conditions have been bad not only for the Tribune force but for its customers as well. With a modern new building, the paper will be housed as it should be and the community will have a better paper as a result,” it promised.

According to the headlines, the walls of the Pioneer building, where it was located, were crumbling.

Workers were beginning to organize and fight for fair wages and safe work conditions, and in Kansas this created an opening for groups like the Industrial Workers of the World and the Ku Klux Klan to gain a foothold--but it didn’t last long.

The Tribune also reported on the progress of the ouster suit against the Ku Klux Klan. The article, “30 Klans in State: Organization has thousands of members, attorneys say,” offered the defense’s own accounting of membership dues and distribution of funds from Kansas to Atlanta, Ga.

“The nighties which klan members wear cost only $6.50, according to the admission, and they are manufactured by the Gate City Manufacturing Company of Atlanta,” the AP article stated. “The local klan gets $1 for every nightie; the company gets $3.67 for each individual uniform, and the national order gets $1.83 for each garment.”

The State held the position that the KKK was a foreign corporation doing business in the Kansas without having applied for or been granted a charter to do so. The suit, brought forth by William Allen White, led to his loss of the 1924 gubernatorial election, but would a favorable ruling for the State of Kansas. The Klan appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and continued to operate during the appeal process. The Supreme Court ultimately threw out the request for appeal on the grounds that no federal laws were being violated, thus exhausting all legal means. The success of the suit rallied the spirits of other states of the time. An interesting historical account of the five year ordeal can be found at the Kansas Historical Society website, http://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-quarterly-kansas-battles-the-invisible-empire/13247.

Officially, the Klan was ousted in 1927, but clandestine groups continued to meet, though numbers continued to decline until in the 1930s, most groups no longer mustered enough membership keep going. It wouldn’t be until the beginnings of the Civil Rights Movement that the KKK would make its third wave.

In the April 6 edition, a Topeka story, “Kitchen is released: Tells Court he will answer all questions to best of his ability” ran. “After being in jail one month, being held in contempt of the Kansas supreme court for his refusal to testify at the hearing of the state’s ouster suit against the Ku Klux Klan, H.H. Kitchen, Oklahoma City Klan organizer today informed the court through his attorney that he was ready to comply with the court’s order and answer all questions to the best of his ability. An order for Kitchen’s release was then issued.”

An internet search found no information verifying rumored accounts of a KKK presence in Barton County during this second wave of the Klan during the 1920s. However, Karen Neuforth with the Barton County Historical Society Museum replied in an email that evidence was found while researching the Banta-Nixon murder of July 6, 1921 that the Klan, as well as the IWW, did have a presence in Barton County in the early 1920s, and would burn crosses lit with electric bulbs powered by car batteries up on Bissell’s Point north of Great Bend.