Crop residue is often considered to be a valuable source of nutrients, especially when the residue is from a nitrogen-fixing legume. The nitrogen (N) and other nutrients released from plant residues can be available for use by subsequent crops. However, crop residue can also tie up nutrients – N, in particular – as it is decomposed by soil microorganisms.

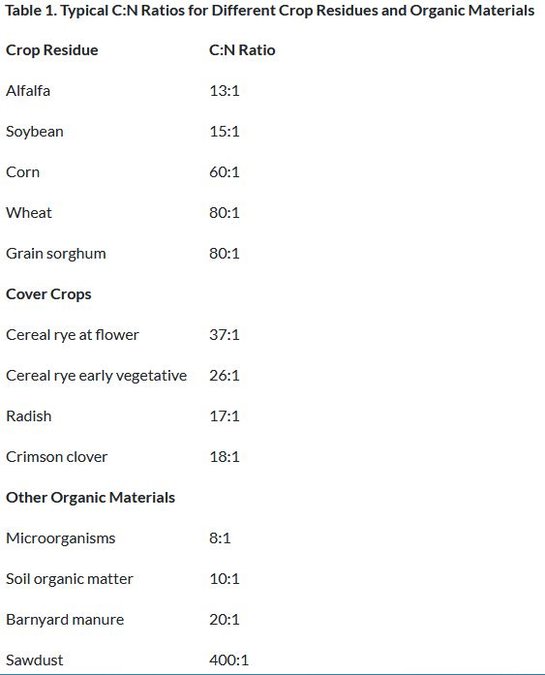

What is the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio? Before the N present in crop residue is available to a subsequent crop, the residue must be decomposed and the N mineralized, or converted to ammonium (an inorganic form of N that crops can use). How quickly crop residue decomposes depends on the residue’s ratio of carbon to nitrogen (C:N). The C:N ratio can vary greatly between different crop residues (Table 1). This ratio is really a measure of the %N in the residue since the proportion of C in crop residues averages around 40%.

The C:N ratio of crops can change depending on the growth stage due to differences in the %N in the plant tissue. Information collected by Tom Roth, agronomist with USDA-NRCS, showed a large difference the C:N ratio of cereal rye clipped in mid-March (~12:1) compared to termination in late April (~24:1). Decomposition will proceed more rapidly for crop residues that have smaller (more narrow) C:N ratios. Depending on the goal of your cover crop, a quicker rate of decomposition may not be desirable.

What determines how and when the N in crop residue, from either a cash crop or a cover crop will be released into the soil? The C:N ratio of the residue is the key factor to look at when determining the timing of N tie-up and release from residue decomposition.

Scenario 1 - In residue a C:N ratio of less than 20:1, soil microorganisms have enough N available in the residue to do their work and residue decomposition proceeds quickly. In that case, organic N is mineralized or released, fairly quickly to the soil inorganic pool (plant available). Most residue with a C:N ratio of less than 20:1 is either a legume or young, lush vegetation, such as wheat prior to jointing.

Scenario 2 - With a C:N ratio above 25:1, N becomes a limiting factor for decomposition. The population of soil microorganisms needed to decompose the residue increases rapidly while consuming N from the soil in the process, if it is available. This uptake of available inorganic N to decompose the residue is called immobilization, or N tie-up. This is a temporary process, and some N may become available during the growing season depending on the residue. The higher the C:N ratio, the longer the N will be tied up. Corn or wheat residue will take longer to decompose as compared to soybean, alfalfa or other legume residues. When the available C or energy begins to run out, the population of soil organisms using the residue as energy will die back, releasing N back to the inorganic pool (mineralization).

Information provided by Dorivar Diaz & Deann Presley, K-State Extension Nutrient & Soil specialists.

Stacy Campbell is an Agriculture and Natural Resources agent for Cottonwood Extension District. Email him at scampbel@ksu.edu or call the Hays office, 785-628-9430.