This is part one of a three part series focusing on youth aging out of foster care.

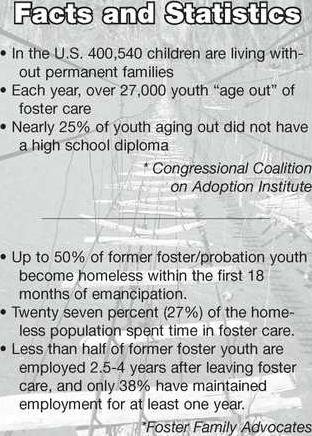

In January, Barton County volunteers with the homeless survey learned first hand that many homeless were once part of the foster care system. Statistics show that children of former fosters have a higher incidence of entering the foster care system themselves.

Aging out foster youth are being encouraged to become active participants in planning for jobs, finances and education after high school. Advocacy groups are working to help them take the first steady steps into adulthood, and hopefully, break the cycle.

Graduation is right around the corner, and all over the country parents will fill bleachers, beaming with pride. While most grads will look into the audience and find their loved ones, there will be some who will lock eyes with someone other than their parents. They are the small but important percentage of youth who “age out” of the foster care system each year. Kansas accounted for 347 of these youth last year.

John and Ann Adims, a Great Bend couple, have been foster parents for several years. They are one of several families licensed and registered with a foster care agency located in Wichita. They agreed to talk with The Great Bend Tribune with the understanding their identity and the identities of the children they care for are protected.

They’ve seen first hand the importance of having a stable, loving home where children can learn to move forward towards a bright future.

When a child enters the foster care system, they’ve had major trauma in their family life, Ann Adims said.

Some of the biggest hurdles the kids need to overcome are the lack of self-esteem and the lack of permanency that comes from moving from home to home. Many foster parents truly wish to make a difference in a child’s life, but not all are so altruistic.

“Some of the kids who come to us tell us stories that will just break your heart,” Adims said. Stories about moving from house to house carrying their belongings in trash bags, or being offered macaroni and cheese night after night while the foster family dined on steak. “It’s is easy to see how some foster kids can begin to feel they are not as valuable as other kids, and begin to have low self-esteem.”

Providing shelter is only one part of being a foster parent. Having a caring adult around to encourage and teach a teen the ropes of living in the adult world can do wonders for self-esteem. In Kansas, most children that enter foster care are eventually returned to their parents. That is in fact the hoped for end game of foster care -- to keep the child safe and work with the parents to reunite the family.

But sometimes this is not possible, and the children will either be placed for adoption or remain in care. Both scenarios can mean an older child will be among those who age out of care each year. In the past, aging out meant an end to support payments to foster care parents or relatives who agreed to foster. Once the money stopped, these young adults found themselves couch-surfing with friends and relatives, uncertain where they would be sleeping the next week, or even a few days later.

While the recent economic downturn that started in 2008 worsened the problem, it also caught the attention of legislators, and new programs were enacted.

Building a bridge

In 2011, the Kansas Youth Advisory Council, made up of youth in foster care and foster care alumni was formed. Today, they promote advocacy and take on the foster care system to improve outcomes for fosters.

Daniel Martin, a foster alumni, has been with the KYAC from the beginning. Today, he works Kansas Department of Children and Families as a program consultant with the National Youth in Transition Database.

“I entered the foster care system when I was 15,” he said. “While there were several moves, some planned and some emergency situations, it wasn’t quite as bad for me. I didn’t have to move every month or every other month.”

Eventually, Martin landed with a foster parent that was a placement for him until he entered an independent living program through Youthville in Wichita.

As a part of the program, first in a group home and then in an apartment type setting, he learned the skills he needed to be able to live on his own, later entering the military and then attending college.

Repairing the holes

The Department of Children and Families assigns an Independent Living coordinator to each youth over the age of 16 to help develop a transition plan that addresses five aspects of life, including education, housing, employment and finances, health and community supports. The KYAC created a transition guide for youth titled “Life Under Construction”. It’s a resource fosters can turn to when creating a plan for their life.The hope is that by creating a plan, the young person can successfully make the leap into independent living.

Fosters are required to form a transition team. Members of the team can include foster parents, Court Appointed Special Advocates, case workers, mentors and other family members. This can be tricky for some fosters. While some youth end up in a stable foster home, others are moved for various reasons and may not have the same foster family or case worker through the entire transition.

This team is critical because for fosters the typical safety net of parents and homelife can have gaping holes in it. Some have trouble getting high school diplomas or G.E.D.s before they age out. If college or vocational school doesn’t work out, or jobs are not forthcoming, there may not be anyone to fall back on for help.

According to Angela deRoca, communications director for the Kansas Department of Children and Families, Independent Living services are available to former fosters ages 18 to 21.

“It’s not uncommon for a youth to age out at 18, decide not to access Independent Living services, and then seek them later.” Currently, the DCF serves 581 young people.

For those who qualify, the state provides a basic safety net. Services such as the extended use of the medical card, a one time $500 living expense subsidy to help with utility deposits, furniture and household supplies and a one time $500 payment for rent and deposit are available to those in need. For those going on to college, there are also programs and scholarships to help pay for tuition, room and board.

That’s good for a start, but the missing component according to Martin is the support from someone who cares.

“I’m talking about emotional support and encouragement,” he said. “Foster youth can do just as much as any other youth does. We just need that support. And you don’t need to be a social worker to do it.”

DeRoca said those interested in mentoring an aging out foster should contact their local DCF office.

--Next, a focus on changes to the foster care system that are improving outcomes for fosters, and how mentors are helping.

Web resource:

Locations of DCF offices: http://www.dcf.ks.gov/services/Pages/DCFOfficeLocatorMap.aspx .

First Steps: Aging out of foster care