Julie Williams is looking for a job — the last one she had was at an escrow service. That was almost 20 years ago. Since then, the 38-year-old from Parker, Colorado, has been working as a stay-at-home mom to her five children.

She and her husband both have college degrees, but Williams' husband lost his job with a wealth management firm in the financial downturn in 2008, and spent a few years looking for new work and trying to start a business. There were several years of struggle, and even though her husband now has a great job with an IT company, things are tighter than she would like. "Even just $150 a week would make a difference," she says, especially if they decide to buy a second car and take on a car payment.

Thirty years ago, the majority of families with children had only one parent working outside the home. Now, two-thirds of couples with kids require a double income to pay the bills.

However, a number of things work against these families: income phase-outs for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and extra costs like child care and transportation can be a burden when both parents work. In some cases, these realities discourage job-seekers like Williams because it's hard to get ahead with a second job, when it requires extra costs of day care or a second car.

It can be a tough time for workers and would-be workers in America, where incomes slid during the recession, and remain 8.3 percent lower than they were in 2007.

Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash. recently introduced the 21st Century Worker Tax Cut Act that favors a minimum wage increase to $10.10 an hour, and champions other factors that would help Americans at the bottom of the income structure earn more. Can a new focus on work help working American families get ahead?

The ways we think about work

The idea that if you work hard and keep your nose clean you can succeed is part of American culture, says Princeton psychology professor Susan Fiske, who studies attitudes about social class. But the reality is that it's hard for many Americans to rise above their circumstances.

At least 10 million people in America are working and still live below the official U.S. poverty line — about $18,530 a year for a mom and two kids, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. People in the service industry, farmers, construction workers and sales people make up a lot of America's working poor.

"Unfortunately, these cultural myths are less true than we would like to believe," says Fiske. Americans like to identify themselves as middle class, but mostly are split between working class and middle class, with 10-20 percent in the extremes.

"Our collective belief is that America offers opportunity, so the system is fair. In a meritocracy, people get what they deserve" says Fiske. But the reality is that people's ability to move above their parents' social class is limited, and no better than in many other countries, she says. About a third of Americans rise above their parents' social class, a third stay the same, and a third move down.

E.J. Dionne, Brookings fellow and professor of government at Georgetown University, ties these attitudes to policy and a reluctance toward moves like raising the minimum wage, when policymakers emphasize the "flaws of the unemployed themselves rather than the cost of economic injustice," writes Dionne.

We have a need to explain the unequal status quo, according to Fiske, and explaining away the poor's misfortunes by assuming that they are lazy allows one to dismiss them.

"When a group is unfortunate, we have a tendency to blame them rather than see situational things that make it difficult for them," she says.

Policy solutions

The idea behind Rep. Patty Murray's bill is not that it would create more work for unemployed Americans, but that it would increase wages for more workers. Murray notes that a second earner often pays a higher tax rate on his or her earnings than the first, which creates disincentives to send a spouse or partner into the workforce. She would resolve this by offering a 20 percent deduction on the second earner's income up to $60,000 a year.

For someone who earns $25,000 a year as a second earner, this would mean $1,250 that goes back into their pocket. The idea, says Murray, is that this could go back toward child care, retirement savings or extra groceries — the things that working-class families struggle to afford.

Murray's bill would also expand one of the most successful anti-poverty programs in place, the Earned-Income Tax Credit, which puts more money back into the bank accounts of low-income earners at tax time. Murray's bill would reduce the eligibility age from 25 to 21 and increase the maximum benefit from $487 to $1,400 a year. "That's real money for someone earning $15,000 a year," says Murray.

The proposal would be covered by existing loopholes in the tax code, to the tune of about $15 billion a year.

Path to change

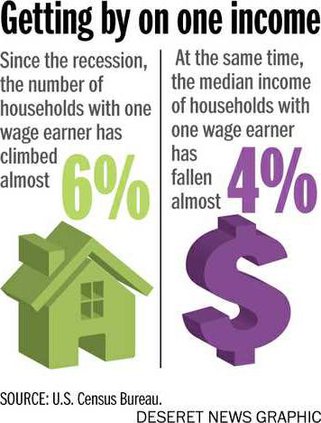

Second-wage earners are now critical to the American economy, not only to keep families afloat, but to provide skilled labor to the workforce. Since the recession, the number of households with one wage earner has climbed almost 6 percent, according to the U.S. Census. At the same time, the median income of households with one wage earner has fallen almost 4 percent.

It's also important for personal growth.

Williams says that she would like to do something in retail, maybe. She likes working with people, and her associate's degree is in communications. Or maybe she would like to try working in an office, or doing event planning. "It's not that I don't need the money," says Williams. "But I'd like to do something fun. I could use some stimulation — I get bored."

Does American policy value work?