Jayne Hitchcock experienced online harassment before Facebook, SnapChat, texting or the Cloud ever existed.

In 1996, Hitchcock was a published author moving back to the U.S. from Japan and was looking for a new literary agent. In an online writers group, Hitchcock learned that many of her fellow writers had been scammed out of thousands of dollars by a fake literary agency. When Hitchcock made a public post in her online writing group telling others to watch out for the agency that was fleecing writers, her detractors impersonated her, eventually even giving out her home address and phone number in posts soliciting sex.

"That's when I really got scared," Hitchcock said. "Because I was really afraid someone would come to my house."

And Hitchcock, who now heads online advocacy group Working to Halt Online Abuse, isn't alone, according to a new study from Pew Research Center this week.

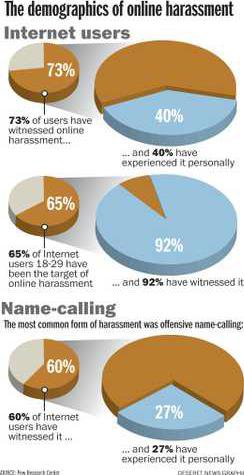

The study found that some form of online harassment — from name-calling to serious threats — affected the majority of Internet users. Seventy-three percent of users have witnessed some form of harassment, while 40 percent have experienced it firsthand.

Personal comments from participants in the study detailed being ridiculed for religious beliefs or political views and that people on social media would "rather throw names than discuss real issues."

Of the 40 percent who said they'd personally been victims of Internet abuse, 27 percent said they'd been called offensive names and 22 percent said detractors had tried to embarrass them on purpose. Eight percent said they'd been physically threatened and 6 percent reported being sexually harassed online.

Study authors Maeve Duggan and Lee Rainie said one of the findings that surprised them the most was how people responded to the harassment and who was impacted most. Sixty percent ignored the harassment, while 40 percent responded in some way, whether engaging their detractor or reporting them to website moderators.

"This is our first deep dive into this subject, so there's a lot of new here," Duggan said. "Young women particularly in the 18-24 age group experience harassment and stalking disproportionately."

The study found that 26 percent of women 18-24 have been stalked online, and 25 percent were the target of online sexual harassment.

Past victims, like Hitchcock and online parenting advocate Sue Scheff, say that the vast majority of people online don't think online harassment can happen to them.

"This happens every single day," Scheff said. "Nobody understands the power of a keystroke. When something like this happens to you, you just want to die. That's the only way I can describe the depth of the hopelessness you feel."

Hitchcock and Scheff offered a number of solutions to address and get help for online harassment, hoping the study will raise awareness about how pervasive online abuse can be.

"Unless they know someone this has happened to, they don't know anything about online harassment," Hitchcock said. "You can't just not go on the Internet. It's like telling a stalking victim to never go outside."

Tell them to stop and don't engage further

The Pew study found that half of Internet users who had experienced harassment didn't know the identity of the person antagonizing them. While the urge to respond to anonymous harassment is natural, Hitchcock says it's best to make sure the other person knows the activity is not OK: "That way, you have proof that you told them to stop," Hitchcock said.

Save everything

Don't wait for things to escalate before documenting the harassment. Scheff and Hitchcock recommend saving every piece of correspondence sent.

Emails can be saved as files, photos can be taken of text messages and screenshots can be taken of suspect instant messages or social media posts. Having all the pieces of the puzzle can help if the police, cellphone company, website administrator or ISP demands evidence before revoking service from someone.

"People don't realize how damaging this can be if they don't nip it in the bud right away," Hitchcock said. "Document everything."

Isolation doesn't work

Think you're safe because you or your children aren't on Facebook or don't have personal email? Think again, Scheff and Hitchcock say.

"Do you have a driver's license? Do you own a home?" Scheff said. "Then you're online."

The best defense is to "claim online real estate" as Scheff calls it. That means going on difference social media outlets and email and making sure no one else has set up a profile with your identity. It's one of the easiest way to ruin someone's online reputation, Scheff says.

"The digital life is here, it's not going away," Scheff said. "If you don't take ownership of your online identity, someone else may."

Offline conversation is key

Scheff says that parents need to keep tabs on their children's online activity just as much as school or who they're hanging out with.

"Just as the conversation flows to, 'Do you have homework,' it should also be, 'How's your cyberlife?'" Scheff said. "You need to have those conversations daily."

Scheff says too often parents wait until a story arises about cyberbullying leading to a suicide before they talk to their children about online safety and by then, it may be too late: "Digital citizenship is as important as potty-training," Scheff said.

Don't fear the 'block' button

When in doubt, hit that 'block' button on Facebook and even on some smartphones.

"You're not being rude protecting yourself," Hitchcock said. "And it's not just about protecting you, it's about protecting all the other people on your friends list or your followers."

Alternatively, other safeguards like changing phone numbers, social media privacy settings or just not giving out personal information helps, too: "Make sure you know the people you're giving this information to," Hitchcock said.

Be a good digital role model

Parents who want their children to be safe and respectful online have to first practice what they preach, Scheff says.

"Our kids are watching how we engage with others. Engaging in heated and angry ways only gives our kids permission to act the same way," Scheff said. "It starts at the top."

Scheff says that ingraining a level of empathy in children from infancy is the best way to fight online harassment long-term.

"That empathy is going to bleed into their online personality," Scheff said. "If a child is taught kindness offline, they’re not going to want to become a troll online."

Email: chjohnson@deseretnews.com

Twitter: ChandraMJohnson

New study highlights prevalence of online harassment