If Kimberly Lonsway told her friends that her house was burglarized over the weekend, they might silently wonder if her door was unlocked, or if she left valuables in plain sight, but out loud they would say, Im so sorry, thats terrible!

Yet, if instead of being robbed, Lonsway told her friend she was sexually assaulted, she believes the responses would be very different.

It would be either A. Are you sure thats what happened? or B. What were you doing?"

Denial and justification, says Lonsway, are the two most common responses when hearing about sexual assault. And the ironic thing is they both cant be true at the same time, but we do it happily," like saying: "That cant be rape, but if it was, it was her fault. Lonway is director of research for End Violence Against Women International, a training organization dedicated to improving sexual assault investigations for victims and pursuing accountability for their assailants.

Beliefs and comments like those are dangerous to the well-being of victims, who are already burdened by feelings of shame, doubt and self-blame. When victims feel unsupported and criticized, experts know they're less likely to go to police, and less likely to seek out healing resources.

While sexual assault continues to be a huge problem across companies, college campuses and communities, experts say they're encouraged by signs that the country is finally willing to talk about it in meaningful ways. They point to the "Start by Believing" campaign, as well as the NFL commercials for the No More" campaign and the White House initiatives Its on Us and Not Alone, plus a recent documentary about assault on college campuses, and even high-profile criminal cases like the ones against Bill Cosby.

(These are) really causing us, for the first time, to truly grapple with sexual assault, said Lonsway. I think it really is an exciting moment right now and terrifying on some level.

Terrifying because experts know that even with the increasing openness, far too many victims still suffer in silence, afraid of being disbelieved or judged.

Some studies suggest that 1 in 5 young women will be sexually assaulted during their college careers (the age group with the highest rates of victimization), yet only a small percentage will come forward to report it. And while the 1 in 5 number is often disputed as being too high, a CDC report from 2010 pointed out that almost 45 percent of women (1 in 2) and 22 percent of men (1 in 5) will experience sexual violence victimization, other than rape, at some point in their lives.

While policy changes have their place, expert say the greatest positive impact on victims of sexual assault will come from friends and family members who have re-evaluated their pre-conceived notions and gone beyond skeptical, judgmental or even naive responses to places of empathy and understanding.

If everyone could decide now, ahead of time, that if someone comes to them (to disclose an assault) theyll provide 100 percent nonjudgmental safe space that would help leaps and bounds, said Kristy Money, a psychologist focused on women's mental health. (Even if they) cant change the system, individuals can commit to something as practical as that, I would hope.

Recovery, not reprimands

The moment an individual is brought into an emergency room having overdosed on heroin is not the time for parents or friends to lecture about illegal drug use or choice of friends.

It's the same with rape victims, says Lonsway.

"When someone has just been raped, that is not the teaching moment," she says. "That is the healing moment. We can all agree that high-risk behavior is more likely to end in bad things, and we can all do things to increase our safety, (and we can talk about those) before and maybe at some point after, but it has no business in that conversation right then. This person has a devastating harm that needs to be dealt with, and everything else can wait."

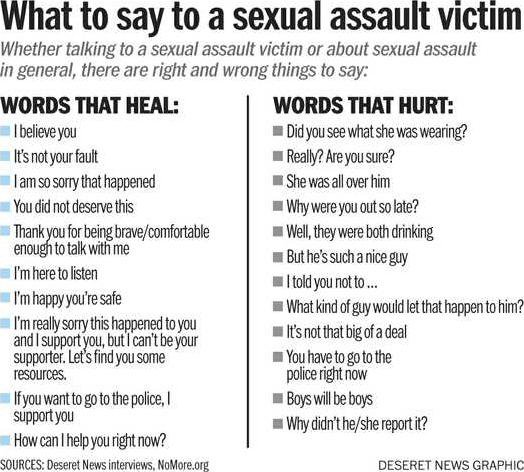

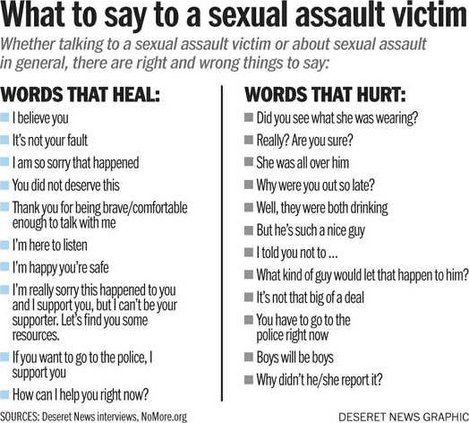

After an assault disclosure, comments or questions like, "Why were you out alone?" or "But he seemed like such a nice guy" or "I told you not to wear that" may be motivated by true concern, but come across as critical and may curb future reporting.

"When thats what your loved one tells you, how on earth are you going to make it to the police, the hospital rape crisis center?" Lonsway said. "The true first responders to sexual assault are people we love, and thats where were failing miserably at this point."

Survivors of sexual assault are already racing through the "if only's" in their minds "if only I had done this," or "if only I had NOT done that," explains Money.

"We heap so much blame upon ourselves already that thats why I don't think it's necessary for anyone else to be doing it," she said.

In a society that expects fairness or justice, experts say, people need to recognize that even for a string of poor decisions, sexual assault is never a reasonable consequence.

"Drinking underage may be a violation of a code somewhere, but it's not a rapeable offense," says Carolyn West, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Washington, Tacoma, and co-editor of the academic journal Sexualization, Media, & Society. "Making maybe not the best choices doesn't mean the punishment is to be sexually assaulted."

The issue of balancing justice and mercy often comes into play on college campuses where victims have broken school codes or even state laws before the assault occurred. Advocates worry that low reporting rates are even lower in communities where victims fear they could be punished for something they did that comes to light as part of their reporting a sexual assault.

In dealing with sexual assault and sexual assault reporting, colleges and communities need to establish their priorities, just like law enforcement does on a daily basis, says Heather Farr Gunnell, former program director for the New Hampshire Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence. With a hierarchy of crimes, authorities have to decide what's most important and if that's ridding their campus, company or community of sexual predators, then they need to create a safe space where victims can come forward and report, knowing they won't be punished for their disclosure, no matter what else happened.

Dealing with sexual assault on campus is challenging, says Sarah McMahon, associate director of the Center on Violence Against Women and Children, and assistant professor at Rutgers School of Social Work

"Certainly universities want to be viewed in a positive light and what we've been trying to argue is that by taking a proactive stand parents will feel safer sending their students, (because the school is) actively addressing the problem, rather than minimizing it," she said.

McMahon, who was involved with a White House Task Force partnership to address the assessment of campus climates related to sexual violence, said administrative discussions are important, and according to her and others, should include talks of amnesty clauses and/or a victim's bill of rights; however, she also encourages individuals to see themselves as a major part of the solution.

She suggests that people learn more about bystander intervention and commit to getting involved if they see an assault begin, or interrupt if they see someone at a party being pressured to drink or go off alone with someone else.

Individuals can confront friends who act in inappropriate ways, point out and reject sexism and sexist language, call people out on rape jokes and speak out against bullying and domestic violence.

"It's all tied together," she says. "If we start a perspective and create communities that promote healthy relationships we all have a role to play in doing that."

Rape myths

Data show that for every 100 rapes committed, only 5 to 20 of those victims will go to police, because "many times survivors dont identify their experience as rape or as a crime, says Jessica Shaw, an assistant professor at Boston College's School of Social Work. We have this common, cultural narrative around what rape is supposed to look like.

Many people still see rape as a stranger-jumping-out-of-the-bushes attack, even though more than half of female rape victims were assaulted by a former or current intimate partner, according to the CDC's National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey.

There's also a perception that sexual assault equals rape, when there's actually a continuum of sexual violence," says McMahon. A large percentage of women and small percentage of men are reporting these experiences of unwanted sexual contact, and thats really problematic.

Whether it's unwanted touching, kissing or intercourse, or even the CDC's defined non-contact unwanted sexual experiences like being flashed, shown sexual photos or forced to show body parts, experts say assault happens when people don't know how to give or get consent, or think something is OK because "they didnt say no.

Define Your Line is a campaign at Texas Tech University designed to spark conversations about consent, because while students may understand its importance, they still don't know what to say or how to say it, says campaign co-founder Rebecca Ortiz, an assistant professor there who studies health communication and representations of sexuality in the media.

The campaign is creating "scripts" or lines that students can use in certain situations, but Ortiz believes the best help for students would be more depictions of healthy consent negotiation unlike most movies, where "passion takes over and they just grab each other and it works, instead of them having that awkward moment (of talking)."

By practicing scripts and "defining their lines" ahead of time, Ortiz hopes students won't feel coerced into unwanted experiences or even gender stereotypes, like women should say no and men should push, or that if a woman says no, shes just being coy and really means yes.

This is not a gender war, Ortiz emphasizes, but an all-encompassing conversation designed to prevent assaults.

Daughters or sons

Parents who know of Shaws research on sexual assault often ask for advice to give their college-bound daughters.

Her answer: What are you telling your sons?

A lot of these conversations are happening in ways that (say) potential victims should guard against sexual assault, says Shaw. I (remind them) that someone cant choose to target themselves. If theyre targeted in that way, its not their fault.

Though true, it's still a difficult message for sexual assault victims to believe, because of society's belief in rape myths, victim blaming and definitional confusion over assault.

Besides, even if someone doesnt blatantly question a victim's story, there are still numerous ways of blaming them, says McMahon.

Its never a victims fault, BUT ,' and then this list of things," she says. " 'You should have seen her, she was all over him, (she was) dressed like a slut, drunk, put herself in a situation.' Its just more subtle sort of language.

People say and think things like this not because theyre heartless, but because without a conscious decision to think differently, they default to a just-world hypothesis, explains Money, a cognitive fallacy that good things happen to good people, and bad things happen to bad people.

So, when a bad thing happens to someone be it maybe a job layoff, a serious illness or financial problem people look for ways to blame it on the victim's choices, and then because they wouldn't make those same choices, they feel protected from the same misfortune.

Such thinking happens all the time with rape and sexual assault, experts say.

If we can find a way that that person who was victimized is to blame somehow, its easy for us to pretend that were safe, says Gunnell. When we acknowledge that theres very little I can do to keep from being victimized perpetrators are very clever, very tricky, and most victims are assaulted by someone they know and trust if I acknowledge that fact, then I lose my sense of control in many ways.

If individuals accept that bad things happen to good people, they become more willing to listen, support and empower not blame those who are struggling, and then hope to receive the same kindness if something bad happens to them, Gunnell says.

Over time, that openness should encourage more women and men to share their histories of sexual violence, says West.

"Then people could understand (that these are) not just ... strangers or people who have made bad decisions, but people who are close to us, people who we know, West says. There would be a different face on sexual assault when its someone you know, rather than a story you read about in the newspaper.

Yet, if instead of being robbed, Lonsway told her friend she was sexually assaulted, she believes the responses would be very different.

It would be either A. Are you sure thats what happened? or B. What were you doing?"

Denial and justification, says Lonsway, are the two most common responses when hearing about sexual assault. And the ironic thing is they both cant be true at the same time, but we do it happily," like saying: "That cant be rape, but if it was, it was her fault. Lonway is director of research for End Violence Against Women International, a training organization dedicated to improving sexual assault investigations for victims and pursuing accountability for their assailants.

Beliefs and comments like those are dangerous to the well-being of victims, who are already burdened by feelings of shame, doubt and self-blame. When victims feel unsupported and criticized, experts know they're less likely to go to police, and less likely to seek out healing resources.

While sexual assault continues to be a huge problem across companies, college campuses and communities, experts say they're encouraged by signs that the country is finally willing to talk about it in meaningful ways. They point to the "Start by Believing" campaign, as well as the NFL commercials for the No More" campaign and the White House initiatives Its on Us and Not Alone, plus a recent documentary about assault on college campuses, and even high-profile criminal cases like the ones against Bill Cosby.

(These are) really causing us, for the first time, to truly grapple with sexual assault, said Lonsway. I think it really is an exciting moment right now and terrifying on some level.

Terrifying because experts know that even with the increasing openness, far too many victims still suffer in silence, afraid of being disbelieved or judged.

Some studies suggest that 1 in 5 young women will be sexually assaulted during their college careers (the age group with the highest rates of victimization), yet only a small percentage will come forward to report it. And while the 1 in 5 number is often disputed as being too high, a CDC report from 2010 pointed out that almost 45 percent of women (1 in 2) and 22 percent of men (1 in 5) will experience sexual violence victimization, other than rape, at some point in their lives.

While policy changes have their place, expert say the greatest positive impact on victims of sexual assault will come from friends and family members who have re-evaluated their pre-conceived notions and gone beyond skeptical, judgmental or even naive responses to places of empathy and understanding.

If everyone could decide now, ahead of time, that if someone comes to them (to disclose an assault) theyll provide 100 percent nonjudgmental safe space that would help leaps and bounds, said Kristy Money, a psychologist focused on women's mental health. (Even if they) cant change the system, individuals can commit to something as practical as that, I would hope.

Recovery, not reprimands

The moment an individual is brought into an emergency room having overdosed on heroin is not the time for parents or friends to lecture about illegal drug use or choice of friends.

It's the same with rape victims, says Lonsway.

"When someone has just been raped, that is not the teaching moment," she says. "That is the healing moment. We can all agree that high-risk behavior is more likely to end in bad things, and we can all do things to increase our safety, (and we can talk about those) before and maybe at some point after, but it has no business in that conversation right then. This person has a devastating harm that needs to be dealt with, and everything else can wait."

After an assault disclosure, comments or questions like, "Why were you out alone?" or "But he seemed like such a nice guy" or "I told you not to wear that" may be motivated by true concern, but come across as critical and may curb future reporting.

"When thats what your loved one tells you, how on earth are you going to make it to the police, the hospital rape crisis center?" Lonsway said. "The true first responders to sexual assault are people we love, and thats where were failing miserably at this point."

Survivors of sexual assault are already racing through the "if only's" in their minds "if only I had done this," or "if only I had NOT done that," explains Money.

"We heap so much blame upon ourselves already that thats why I don't think it's necessary for anyone else to be doing it," she said.

In a society that expects fairness or justice, experts say, people need to recognize that even for a string of poor decisions, sexual assault is never a reasonable consequence.

"Drinking underage may be a violation of a code somewhere, but it's not a rapeable offense," says Carolyn West, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Washington, Tacoma, and co-editor of the academic journal Sexualization, Media, & Society. "Making maybe not the best choices doesn't mean the punishment is to be sexually assaulted."

The issue of balancing justice and mercy often comes into play on college campuses where victims have broken school codes or even state laws before the assault occurred. Advocates worry that low reporting rates are even lower in communities where victims fear they could be punished for something they did that comes to light as part of their reporting a sexual assault.

In dealing with sexual assault and sexual assault reporting, colleges and communities need to establish their priorities, just like law enforcement does on a daily basis, says Heather Farr Gunnell, former program director for the New Hampshire Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence. With a hierarchy of crimes, authorities have to decide what's most important and if that's ridding their campus, company or community of sexual predators, then they need to create a safe space where victims can come forward and report, knowing they won't be punished for their disclosure, no matter what else happened.

Dealing with sexual assault on campus is challenging, says Sarah McMahon, associate director of the Center on Violence Against Women and Children, and assistant professor at Rutgers School of Social Work

"Certainly universities want to be viewed in a positive light and what we've been trying to argue is that by taking a proactive stand parents will feel safer sending their students, (because the school is) actively addressing the problem, rather than minimizing it," she said.

McMahon, who was involved with a White House Task Force partnership to address the assessment of campus climates related to sexual violence, said administrative discussions are important, and according to her and others, should include talks of amnesty clauses and/or a victim's bill of rights; however, she also encourages individuals to see themselves as a major part of the solution.

She suggests that people learn more about bystander intervention and commit to getting involved if they see an assault begin, or interrupt if they see someone at a party being pressured to drink or go off alone with someone else.

Individuals can confront friends who act in inappropriate ways, point out and reject sexism and sexist language, call people out on rape jokes and speak out against bullying and domestic violence.

"It's all tied together," she says. "If we start a perspective and create communities that promote healthy relationships we all have a role to play in doing that."

Rape myths

Data show that for every 100 rapes committed, only 5 to 20 of those victims will go to police, because "many times survivors dont identify their experience as rape or as a crime, says Jessica Shaw, an assistant professor at Boston College's School of Social Work. We have this common, cultural narrative around what rape is supposed to look like.

Many people still see rape as a stranger-jumping-out-of-the-bushes attack, even though more than half of female rape victims were assaulted by a former or current intimate partner, according to the CDC's National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey.

There's also a perception that sexual assault equals rape, when there's actually a continuum of sexual violence," says McMahon. A large percentage of women and small percentage of men are reporting these experiences of unwanted sexual contact, and thats really problematic.

Whether it's unwanted touching, kissing or intercourse, or even the CDC's defined non-contact unwanted sexual experiences like being flashed, shown sexual photos or forced to show body parts, experts say assault happens when people don't know how to give or get consent, or think something is OK because "they didnt say no.

Define Your Line is a campaign at Texas Tech University designed to spark conversations about consent, because while students may understand its importance, they still don't know what to say or how to say it, says campaign co-founder Rebecca Ortiz, an assistant professor there who studies health communication and representations of sexuality in the media.

The campaign is creating "scripts" or lines that students can use in certain situations, but Ortiz believes the best help for students would be more depictions of healthy consent negotiation unlike most movies, where "passion takes over and they just grab each other and it works, instead of them having that awkward moment (of talking)."

By practicing scripts and "defining their lines" ahead of time, Ortiz hopes students won't feel coerced into unwanted experiences or even gender stereotypes, like women should say no and men should push, or that if a woman says no, shes just being coy and really means yes.

This is not a gender war, Ortiz emphasizes, but an all-encompassing conversation designed to prevent assaults.

Daughters or sons

Parents who know of Shaws research on sexual assault often ask for advice to give their college-bound daughters.

Her answer: What are you telling your sons?

A lot of these conversations are happening in ways that (say) potential victims should guard against sexual assault, says Shaw. I (remind them) that someone cant choose to target themselves. If theyre targeted in that way, its not their fault.

Though true, it's still a difficult message for sexual assault victims to believe, because of society's belief in rape myths, victim blaming and definitional confusion over assault.

Besides, even if someone doesnt blatantly question a victim's story, there are still numerous ways of blaming them, says McMahon.

Its never a victims fault, BUT ,' and then this list of things," she says. " 'You should have seen her, she was all over him, (she was) dressed like a slut, drunk, put herself in a situation.' Its just more subtle sort of language.

People say and think things like this not because theyre heartless, but because without a conscious decision to think differently, they default to a just-world hypothesis, explains Money, a cognitive fallacy that good things happen to good people, and bad things happen to bad people.

So, when a bad thing happens to someone be it maybe a job layoff, a serious illness or financial problem people look for ways to blame it on the victim's choices, and then because they wouldn't make those same choices, they feel protected from the same misfortune.

Such thinking happens all the time with rape and sexual assault, experts say.

If we can find a way that that person who was victimized is to blame somehow, its easy for us to pretend that were safe, says Gunnell. When we acknowledge that theres very little I can do to keep from being victimized perpetrators are very clever, very tricky, and most victims are assaulted by someone they know and trust if I acknowledge that fact, then I lose my sense of control in many ways.

If individuals accept that bad things happen to good people, they become more willing to listen, support and empower not blame those who are struggling, and then hope to receive the same kindness if something bad happens to them, Gunnell says.

Over time, that openness should encourage more women and men to share their histories of sexual violence, says West.

"Then people could understand (that these are) not just ... strangers or people who have made bad decisions, but people who are close to us, people who we know, West says. There would be a different face on sexual assault when its someone you know, rather than a story you read about in the newspaper.