WASHINGTON (AP) — Ice cream lovers beware: The government knows you're unlikely to stop after half a cup.

New nutrition labels proposed Thursday for many popular foods, including ice cream, aim to more accurately reflect what people actually eat. And the proposal would make calorie counts on labels more prominent, too, reflecting that nutritionists now focus more on calories than fat.

For the first time, labels also would be required to list any sugars that are added by manufacturers.

In one example of the change, the estimated serving size for ice cream would jump from a half cup to a cup, so the calorie listing on the label would double as well.

The idea behind the change, the first overhaul of the labels in two decades, isn't that the government thinks people should be eating twice as much; it's that they should understand how many calories are in what they already are eating. The Food and Drug Administration says that, by law, serving sizes must be based on actual consumption, not some ideal.

"Our guiding principle here is very simple, that you as a parent and a consumer should be able to walk into your local grocery store, pick up an item off the shelf and be able to tell whether it's good for your family," said first lady Michelle Obama, who joined the FDA in announcing the proposed changes at the White House.

Mrs. Obama made the announcement as part of her Let's Move initiative to combat child obesity, which is marking its fourth anniversary. On Tuesday, she announced new Agriculture Department rules that would reduce marketing of less-healthful foods in schools.

The new labels would be less cluttered. FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg called them "a more user-friendly version."

But they are probably several years away. The FDA will take comments on the proposal for 90 days, and a final rule could take another year. Once it's final, the agency has proposed giving industry two years to comply.

The agency projects food companies will have to pay around $2 billion to revise labels. Companies have resisted some of the changes in the past, including listing added sugars, but the industry is so far withholding criticism.

Pamela Bailey of the Grocery Manufacturers Association, the industry group that represents the nation's largest food companies, called the proposal a "thoughtful review."

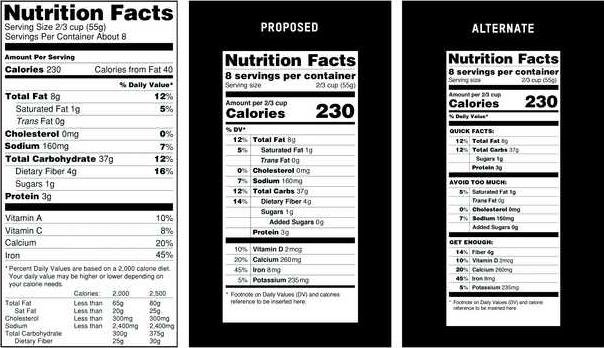

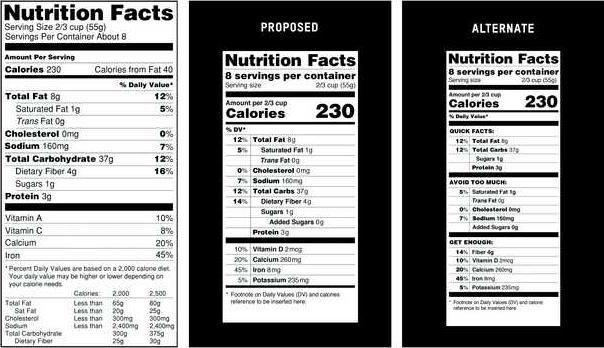

It is still not yet clear what the final labels will look like. The FDA offered two labels in its proposal — one that looks similar to the current version but is shorter and clearer and another that groups the nutrients into a "quick facts" category for things like fat, carbohydrates, sugars and proteins.

There also would be an "avoid too much" category for saturated fats, trans fats, cholesterol, sodium and added sugar, and a "get enough" section with vitamin D, potassium, calcium, iron and fiber. Potassium and vitamin D are would be additions, based on current thinking that Americans aren't getting enough of those nutrients. Vitamin C and vitamin A listings are no longer required.

Both versions list calories above all of those nutrients in large, bold type.

Serving sizes have long been misleading, with many single-serving packages listing themselves as multiple servings, so the calorie count appears lower.

Under the proposed rules, both 12-ounce and 20-ounce sodas would be considered one serving, and many foods that are often eaten in one sitting — a bag of chips, a can of soup or a frozen entree, for example — would either be newly listed as a single serving or would list nutrient information both by serving and by container.

The inclusion of added sugars to the label was one of the biggest revisions. Nutrition advocates have long asked for that line on the label because it's impossible for consumers to know how much sugar in an item is naturally occurring, like that in fruit and dairy products, and how much is added by the manufacturer. Think an apple vs. apple sauce, which comes in sweetened and unsweetened varieties.

According to the Agriculture Department's 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, added sugars contribute an average of 16 percent of the total calories in U.S. diets. Though those naturally occurring sugars and the added sugars act the same in the body, the department says the added sugars are just empty calories while naturally occurring ones usually come along with other nutrients.

David Kessler, who was FDA commissioner when the first Nutrition Facts labels were unveiled in the early 1990s, said he thinks focusing on added sugars and calories will have a public health benefit. He said the added sweetness, like added salt, drives overeating. And companies will adjust their recipes to get those numbers down.

While some people ignore the panels, there's evidence that more are reading them in recent years as there has been a heightened interest in nutrition. An Agriculture Department study released earlier this year said 42 percent of working adults used the panel always or most of the time in 2009 and 2010, up from 34 percent two years earlier.

CHECK THE LABEL

New food labels aim to make healthy shopping easy