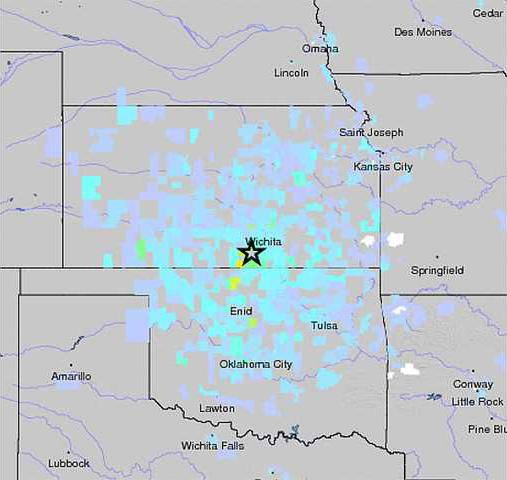

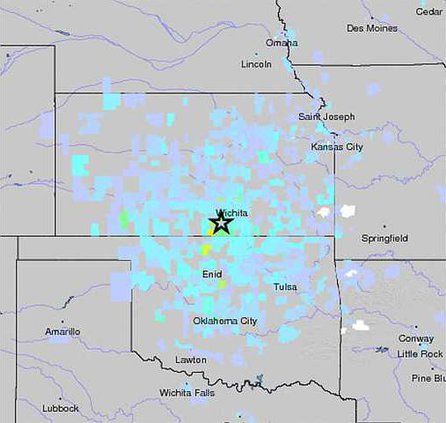

Wednesday afternoon, people reported feeling the ground shake as far north as Manhattan when a 4.8 magnitude earthquake occurred near Conway Springs, located between 80 and 90 miles from the Oklahoma border, west of Wichita.

It’s not the first time in recent history Kansans in the southern part of the state have felt what some describe as a bouncing or shimmying of the floor. A hundred miles away, in Great Bend, Tribune employees felt the earth move, and responses on social media immediately following the event indicated others in the area, and as far away as Salina also felt the tremor.

“People are calling Sierra Club asking for help,” wrote Joe Spease, fracking chairperson with the Kansas Sierra Club, in a statement sent to the media Thursday morning. “Their homes are damaged and they don’t know what to do.”

He cited the Kansas State Task Force on Induced Seismicity.

USGS convinced

injections well activity behind quakes

“These quakes are definitely caused by the disposal of toxic fracking waste fluids into injection wells,” Spease said. “The USGS issued a study in mid-September linking the cause and effect.”

That study, released by the United States Geological Survey in September, 2014, was conducted at the Raton Basin, which includes a vast area including Southern Colorado and Northern New Mexico, found that the deep injection of wastewater from the coal-bed methane field is responsible for inducing the majority of the seismicity since 2001.

Three lines of evidence were cited. First, the marked increase in earthquakes in the area. Only one M>4 earthquake occurred in the area between 1972 and July, 2001. Between Aug. 2001 and 2013, 12 occurred. Statistically, the possibility of this occurring naturally was only 3.0 percent, according to the study.

Second, the short distance from injection wells and the shallow origin of the earthquakes indicates they occurred because of injection activity. The surrounding area saw no change in earthquake activity.

Third, the study cited the high volume and high rate of the water injected into wells in the area.

Yvonne Cather, president of the Kansas Sierra Club, commented on the task force’s draft action plan which was sent to select groups on Sept. 1, requesting comments, Spease said. The draft came to the attention of the Sierra Club near the end of the comment period. The organization requested and received a 10-day extension of the deadline.

The authors of the plan asked the legislature to pay for earthquake monitoring equipment and for additional research into the geological structures underlying Kansas.

“We have many concerns about the action plan,” Cather wrote. “The primary problem we see is that the plan does little to address the property damage resulting from earthquakes caused by disposal of fracking waste fluids into injection wells.”

Protecting the people

The report includes a response plan when seismic activity is detected. The steps are lengthy, but if it is ultimately determined an earthquake was induced, “the KGS, KCC, and KDHE will evaluate all available data and determine whether any of the regulatory remedies available under current statutory authorities are necessary,” according to the plan. Cather is correct in that the plan does not offer remedies to property owners.

That’s because, according to Ryan Hoffman, it is outside the jurisdiction and authority of the KCC to do so. Hoffman is the director of the Conservation Division of the Kansas Corporation Commission, and one of the three task force members.

The KCC regulates Class II injection wells, the type that are the focus of the induced seismicity study. Rex Buchanan, the interim director of the Kansas Geological Survey, and Mike Tate, chief of the Bureau of Water with the Kansas Department of Health and Environment, are the other two members.

The task force was formed, with the protection of the people of Kansas in mind, to find the cause of this induced seismicity, and determine how to stop it, Hoffman said.

“If it should be determined a particular well is at fault, the commission has the authority to revoke a permit, to make the operator plug a well, and to impose fines if necessary,” he said. “Damages would be for the courts to decide.”

If the commission were to make a decision against a well owner, it could be appealed, he added.

According to Buchanan, while an increase in seismic activity correlates to increases in injection well activity, it doesn’t prove it’s the cause of the activity. To determine that, better monitoring needs to occur.

Kansas, never before a hotbed of earthquake activity, does not have its own state-supported seismic network. It relies on two permanent seismic monitors located in-state and operated by the USGS, as well as information from the Oklahoma Geological Survey. And while the USGS has set up temporary monitors in several locations in southern Kansas, the KSGS would requested additional permanent monitors as well as a portable array system to better cover and pinpoint where and what is triggering earthquakes.

To insure or not to insure?

And while Cather hasn’t yet received reports of damage from Wednesday’s earthquake, she has received calls from those who have experienced damage from previous earthquakes.

“One person from Sedgwick County discovered her foundation was cracked, and it will cost her $13,000 to have it fixed,” Cather said. “The insurance company won’t cover the damage.”

According to Neil Cordre, an agent with Farm Bureau Insurance in Great Bend, earthquake coverage is available as additional coverage. However, the company has issued a temporary moratorium on issuing riders on existing policies. New policies, however, are considered an acceptable risk, he said.

This, he said, is to ensure policy owners don’t purchase a policy they don’t plan to hold onto long term. The policies aren’t sold very often, he said, but he has received a few calls in the past day inquiring about their availability. Different insurance companies will have different risk tolerances, so it’s important to ask plenty of questions, he said.

Insurance adjusters, the gatekeepers between policyholders and their insurance companies, are trained to determine if damage is caused by seismic activity, or simply settling over time, Cordre said. But determining if the seismic activity is naturally occurring or caused by activity from oil and gas companies requires scientific and technical expertise.

Great Bend is not located close to major fault lines close to this area, and high-volume horizontal fracking is not an issue in the immediate vicinity.

Eathquake damage worries homeowners