By Beccy Tanner

Wichita Eagle

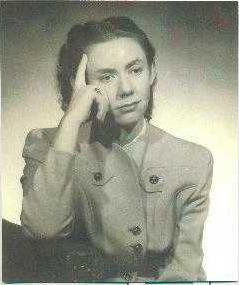

Joan Bondurant grew up in Great Bend.

Her childhood was far from exceptional. Her father was the owner of a hardware store. Her mother was a voracious reader. She loved music and envisioned herself as one day becoming a music critic.

Instead, she became an international spy. She was a member of the Office of Strategic Services, of which other members included the likes of Julia Child and Marlene Dietrich during World War II. The OSS was the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency.

Bondurant became fluent in Japanese, transcribing messages and documents for the United States until after the war. Then, the U.S. sent her to India. She became fluent in Hindi and became friends with Mahatma Gandhi. She also became fascinated with satyagraha, a philosophy of nonviolent resistance. In 1958, she wrote the book “Conquest of Violence: The Gandhian Philosophy of Conflict.”

“She became the top political scientist in the United States of America on Gandhi’s tactics,” said Marty Keenan, a political science instructor at Central Community College in Hastings, Neb., and an attorney in Great Bend. Keenan is writing a book on Bondurant’s life. She is also featured in 1998 book called “Women of the OSS: Sisterhood of Spies,” by Elizabeth P. McIntosh.

In 1971, 13 years after “Conquest of Violence” was published, Daniel Ellsberg released the Pentagon Papers, a study of U.S. decisions in regards to the Vietnam War. Ellsberg would cite Bondurant’s book as his inspiration.

She was born Dec. 16, 1918, at the family’s home at 2320 Broadway in Great Bend. She was exceptional in math, English, geography and history. She graduated valedictorian from Great Bend High School in 1937 and attended the University of Michigan, Keenan said.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Bondurant, who was then a senior at the University of Michigan, decided she wanted to do something to support the war effort. She took a Japanese-language crash course that was for men only.

“She sat outside the classroom and persisted until they let her take the class,” Keenan wrote in an e-mail to The Eagle. “She knew nothing about Japanese.”

But she had previously learned Italian, German, Spanish, Latin and French and believed her skills and ear as a musician would help her learn the language, Keenan said.

Bondurant and her friend and partner, Maureen Patterson, each mastered half of the Japanese written language. They were assigned to work in San Francisco, collecting photos and translating Japanese documents found on the West Coast.

“We were bombing targets, so they were looking for photos, anything,” Keenan said. “She and Maureen would go out and cover by saying they were with the ‘American Pictorial Agency’ and ask for photos of Japan. They went to Christian Missionaries who had returned from Japan.”

They also would examine documents and papers the U.S. government had seized from Japanese-American families sent to internment camps.

In May 1944, the two women were sent to New Delhi to continue their spying efforts. In January 1945, they were told to change their focus from Japan to India. British India was crumbling; their assignment was to get to know the would-be founders of the new government, Keenan said.

Bondurant witnessed riots in New Delhi between Muslims and Sikhs when disciples of Gandhi’s nonviolence philosophy successfully defied the government and put an end to the riots.

She would later return to the United States. In 1952, she received her doctorate in political science from the University of California-Berkley.

Her book on Gandhi became the first book by a Western political scientist to look at the significance of Gandhi and the theory and practice of nonviolent resistance.

“She broke the gender barriers,” Keenan said. “She made a great contribution to her country, but then she turned around and made an even greater contribution to the world by synthesizing Gandhi’s teachings. She told him that she wanted to spend her life studying his tactics and life; he told her that ‘My life should not be studied, but practiced.”

In New York’s University of Rochester, there is a Joan Bondurant Collection at the Rush Rhees Library. One piece in the collection is an autographed copy of Ellsberg’s “Papers On The War.” It is addressed to Bondurant, dated March 24, 1976, and says: “...book was crucial to my decision to release the Pentagon Papers – With Love, Daniel Ellsberg.”

She died on Sept. 12, 2006, in Tucson.