The Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 is the nation’s benchmark civil rights legislation, and it continues to resonate in America. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. Passage of the Act ended the application of “Jim Crow” laws, which had been upheld by the Supreme Court in the 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson, in which the Court held that racial segregation purported to be “separate but equal” was constitutional. The Civil Rights Act was eventually expanded by Congress to strengthen enforcement of these fundamental civil rights.

Source: U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary

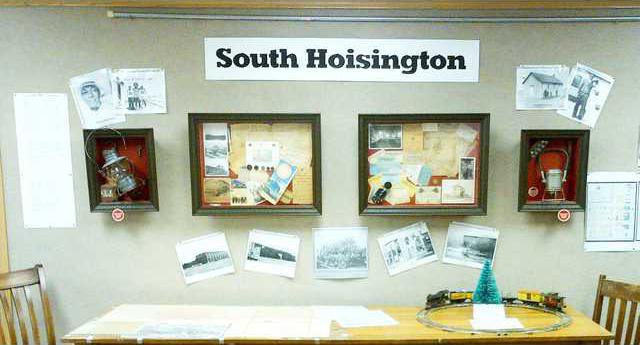

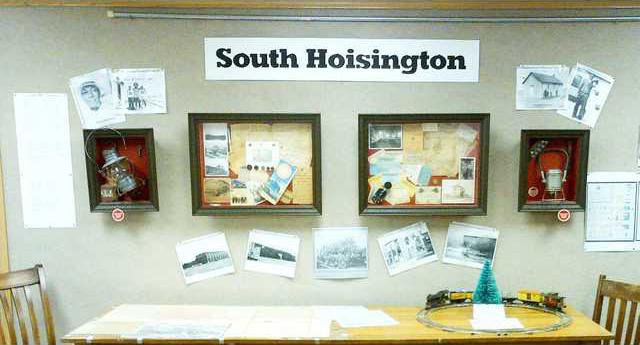

A project to preserve the history of South Hoisington started with a mini-grant from the Kansas Humanities Council but grew into a major undertaking for the Barton County Historical Society. The historical society has until Jan. 31 to fulfill the terms of the grant, but research on the community will continue, said Beverly Komarek, executive director of the historical society’s museum.

Already, the museum has a small exhibit of maps, photos and memorabilia collected for the exhibit, “South Hoisington: Stories from the Other Side of the Tracks.”

The Kansas Humanities Council’s grant was part of a national project titled “The Civil War to Civil Rights,” coordinated by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Park Service and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. In 2014, the project will celebrate the 50th anniversary of The Civil Rights Act of 1964.

South Hoisington was platted but never incorporated or annexed into the city of Hoisington, said Karen Neuforth, research coordinator for the museum. Its residents were mostly African Americans, who first came to build the Missouri-Pacifc Railroad but weren’t allowed to reside in Hoisington. A few Mexican immigrants also lived “south of the tracks.” A notation on the 1940 Census records shows five Mexican families were living in boxcars.

Outside of the city limits, the area did not receive the benefits of paved streets or other services, and was prone to flooding. It also wasn’t served by city law enforcement, and some entrepreneurs made their livings offering alcohol, gambling and prostitution. A business known to provide every vice was named South Haven, but was better known as The Big House. People who know nothing else about South Hoisington have heard of The Big House, but there was also a grocery store, gas station, church, sale barn and cafe, Neuforth said.

Researchers knew there was more to the story, and set out to get oral histories from former residents. Angela Bates from the Nicodemus Historical Society provided training on how to complete racially sensitive oral histories.

“Locally, we have certain views about South Hoisington,” Komarek said. “But we wanted the stories of people who lived there.”

The Hoisington Historical Society has helped with the project tremendously, said Tracy Aris of Lisle, Ill. The daughter of Komarek, she is one of many working on the grant project.

The story of South Hoisington begins with the westward expansion of the railroad, Aries said. Barton County businessmen had founded the town of Hoisington to attract the Kansas and Colorado Railroad – later to become the Missouri Pacific – to the area. African American families came to work on the railroad, but weren’t allowed to live in the city. South Hoisington accounted for the county’s largest population growth until World War II, when the air base was constructed.

South Hoisington survived through two World Wars, the Great Depression and Prohibition.

The town exists today in fragments of history, and in the memories and stories of people who lived there or interacted with those who did.