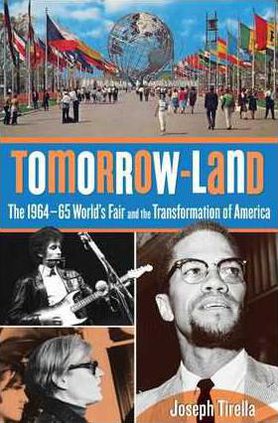

"TOMORROW-LAND: The 1964-65 World's Fair and the Transformation of America," by Joseph Tirella, Lyons Press, $26.95, 360 pages (nf)

It may be difficult for those born after 1984 to imagine, but there was a time when one could not find out everything about a distant culture with the click of a mouse. No Internet could help because, well, no Internet existed.

Instead, people relied on books, magazines and the still relatively young thing called television to aid in their understanding. The jet aircraft made globe-hopping more possible, not only sending writers and photographers to faraway places but also bringing the results of their searches home much more quickly.

Some of those results coalesced in a portion of 1,200 acres of swampy landfill in the middle of the borough of Queens, one of five New York City counties, in a two-year spectacle that vied with the "British invasion" of the Beatles and the American revolution of Bob Dylan as game-changers for society.

During those years, an aging New York bureaucratic titan named Robert Moses was calculating what he'd hoped would be his last greatest work. Moses, preternaturally brilliant in urban planning and in political skills, had transformed New York City beyond what anyone might have imagined. His parkways sliced through Brooklyn and Queens, pulsing out toward Long Island's Nassau and Suffolk counties, home to new "bedroom communities" of single-family homes and of Jones Beach. It was Moses' transformation of shoreline into a clean summertime escape from the city's grit and sweat.

Moses' highway construction displaced hundreds of families and effectively destroyed some of New York's older neighborhoods. He was feared somewhat more than loved, earning the sobriquet "Master Builder," and not always as a badge of honor.

Knowing his career would soon end, Moses wanted a crowning achievement, an ultra-high note on which to leave. For him, it would be a two-year extravaganza reprising the famed 1939-40 New York World's Fair, perhaps most remembered as the birthplace of regular television broadcasting. Moses wanted a 25th-anniversary event to herald even more of the future than the pre-war celebration did.

In "Tomorrow-Land: The 1964-65 World's Fair and the Transformation of America," Joseph Tirella, a Queens native, chronicles not only Moses' life and many struggles to bring the fair to life but also the cultural tumult that surrounded the fair's two years of existence. President John F. Kennedy, who attended the groundbreaking for the event, was assassinated five months before the fair opened. The Beatles' tumultuous "Ed Sullivan Show" appearance was a very fresh memory and the U.S. civil rights movement was in full throttle. Lyndon B. Johnson, Kennedy's successor, was ramping up American involvement in a far-off nation called South Vietnam, eventually leading to massive antiwar demonstrations.

As Tirella summarizes: "While the Fair promised a new world of peace, understanding and fraternity among nations, millions of young Americans who had already enjoyed Moses' exhibition saw through the illusion. Many more of them, the more politically savvy, felt that the Tomorrow-Land world of the Fair, no matter how noble its intentions, was a technological chimera bought and paid for by the political and corporate elites who had waged the Cold War, had their finger on the A-bomb, had resisted civil rights for millions of Americans, and had launched a new war in Vietnam."

Tirella tells the story with an eye for detail and brings forth historic facts about how the fair came to be, despite bruising conflicts in many quarters. Pairing the tale of "Tomorrow-Land," a theme from the General Motors' pavilion, with the roiling societal conflicts is a good contrast and puts the fair in its place within that era.

Tirella has a rather graphic retelling of things — four-letter words litter several chapters, bordering on the gratuitous — in this otherwise good history and gripping tale

Before Google, 1964 World's Fair opened U.S. to diverse cultures