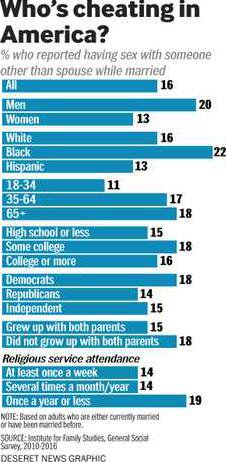

While most people never cheat on a spouse, a new analysis finds patterns in infidelity. Men are more apt to cheat than women. Adults who grew up in homes where their parents didn't stay together cheat more often than those raised in intact families. And people who attend religious services are more likely to stay true to their spouses than those who seldom or never attend.

Sexual impropriety is on America's mind with news reports of sexual harassment and related issues, and that prompted the analysis, said Institute for Family Studies director of research Wendy Wang, who analyzed General Social Survey data from 2010-2016 to reach her conclusions.

Wang looked at people who have ever been married to compare who cheats and who doesn't based on diverse factors that included race, age, gender, political party and more.

"There are consequences to cheating," Wang noted. "It has impact on relationships and can be very detrimental. It's hard to find statistics on what percentage of divorce is because someone cheated. But those who have cheated are more likely to be divorced currently. It's closely linked. And of course, some will marry again, maybe cheat again. Just the fact that one has cheated in the past is related to marital status."

Most married folks do not have extramarital affairs. Experts say that rates of infidelity have hovered pretty consistently around 16 percent overall for some time. Still, it's a hot topic, and several studies have made the news recently.

But even describing what cheating is has become more complicated than in the past as definitions and attitudes have changed over time. The most recent "Ten Today" poll conducted for the Deseret News found opinions vary about what even constitutes cheating. While that poll explored a range of possible definitions, Wang's analysis looked just at those who reported having sex with someone other than their spouse while they were married.

Politics, race and religion

Wang said one of her most unusual findings was that political party matters, but only for women. Females who are Democrats are more likely to commit adultery than female Republicans, but men in either party are about equally likely to be unfaithful.

Education isn't relevant, she noted, but race is. Blacks are slightly more likely to cheat (22 percent) than are whites (16 percent), who are more likely to cheat than people who are Hispanic (13 percent).

Of the factors she analyzed, religious attendance was the strongest predictor of not cheating for both men and women. The "kind of people who attend religious services" rather than the particular religion or their gender is most predictive, she noted. "It is consistently predictive" of whether one is faithful or not.

Wang found little similarity between men and women in terms of who cheats. When she controlled for other factors, she found men's rates of infidelity were not less because they were Republican or because their family growing up remained intact. Race, age and going to religious services did, however, lower the number who cheated.

"By comparison, party ID, family background and religious service attendance are still significant factors for cheating among women, while race, age and educational attainment are not relevant factors," she wrote. "In fact, religious service attendance is the only factor that shows consistent significance in predicting both men and womens odds of infidelity."

Age patterns

Who cheated and when changed by age. Between age 18 and 29, slightly more women actually cheated, 11 percent compared to 10 percent for men. After that, men cheat in higher numbers and the gap widens among older age groups. Among octogenarians, 24 percent of men have cheated on a spouse, compared to just 6 percent of women. Some of that difference may be that elderly women are less likely to be married, compared to elderly men. The unmarried are not considered cheaters.

The largest percentage of infidelity for women is in their 60s (16 percent), while for men the peak is in their 70s (26 percent).

That cheating is higher among older Americans may surprise a lot of people, but it's a fact well known to University of Utah sociologist Nicholas Wolfinger, who earlier this year analyzed age data on infidelity and noted big changes in who cheats. Since 2000, older Americans report more cheating. Younger Americans report less. His findings were also published on a blog of the Institute for Family Studies.

Wolfinger said that around the year 2004, cheating rates reported by people in their mid-50s and 60s were 5 to 6 percentage points higher than those reported by younger adults.

While his analysis didn't show cause, he told the Deseret News it was likely it reflected traits of that generation, which came of age during the so-called sexual revolution. Creation of medications like Viagra and loosening social mores likely contributed to the increase as well, he said.

Wang's new analysis found a somewhat different timeline. Like Wolfinger, she found women born in the 1940s and 1950s were more likely to cheat, but for men, the highest percentage was among those born in the 1930s and 1940s, she said.

Sexual impropriety is on America's mind with news reports of sexual harassment and related issues, and that prompted the analysis, said Institute for Family Studies director of research Wendy Wang, who analyzed General Social Survey data from 2010-2016 to reach her conclusions.

Wang looked at people who have ever been married to compare who cheats and who doesn't based on diverse factors that included race, age, gender, political party and more.

"There are consequences to cheating," Wang noted. "It has impact on relationships and can be very detrimental. It's hard to find statistics on what percentage of divorce is because someone cheated. But those who have cheated are more likely to be divorced currently. It's closely linked. And of course, some will marry again, maybe cheat again. Just the fact that one has cheated in the past is related to marital status."

Most married folks do not have extramarital affairs. Experts say that rates of infidelity have hovered pretty consistently around 16 percent overall for some time. Still, it's a hot topic, and several studies have made the news recently.

But even describing what cheating is has become more complicated than in the past as definitions and attitudes have changed over time. The most recent "Ten Today" poll conducted for the Deseret News found opinions vary about what even constitutes cheating. While that poll explored a range of possible definitions, Wang's analysis looked just at those who reported having sex with someone other than their spouse while they were married.

Politics, race and religion

Wang said one of her most unusual findings was that political party matters, but only for women. Females who are Democrats are more likely to commit adultery than female Republicans, but men in either party are about equally likely to be unfaithful.

Education isn't relevant, she noted, but race is. Blacks are slightly more likely to cheat (22 percent) than are whites (16 percent), who are more likely to cheat than people who are Hispanic (13 percent).

Of the factors she analyzed, religious attendance was the strongest predictor of not cheating for both men and women. The "kind of people who attend religious services" rather than the particular religion or their gender is most predictive, she noted. "It is consistently predictive" of whether one is faithful or not.

Wang found little similarity between men and women in terms of who cheats. When she controlled for other factors, she found men's rates of infidelity were not less because they were Republican or because their family growing up remained intact. Race, age and going to religious services did, however, lower the number who cheated.

"By comparison, party ID, family background and religious service attendance are still significant factors for cheating among women, while race, age and educational attainment are not relevant factors," she wrote. "In fact, religious service attendance is the only factor that shows consistent significance in predicting both men and womens odds of infidelity."

Age patterns

Who cheated and when changed by age. Between age 18 and 29, slightly more women actually cheated, 11 percent compared to 10 percent for men. After that, men cheat in higher numbers and the gap widens among older age groups. Among octogenarians, 24 percent of men have cheated on a spouse, compared to just 6 percent of women. Some of that difference may be that elderly women are less likely to be married, compared to elderly men. The unmarried are not considered cheaters.

The largest percentage of infidelity for women is in their 60s (16 percent), while for men the peak is in their 70s (26 percent).

That cheating is higher among older Americans may surprise a lot of people, but it's a fact well known to University of Utah sociologist Nicholas Wolfinger, who earlier this year analyzed age data on infidelity and noted big changes in who cheats. Since 2000, older Americans report more cheating. Younger Americans report less. His findings were also published on a blog of the Institute for Family Studies.

Wolfinger said that around the year 2004, cheating rates reported by people in their mid-50s and 60s were 5 to 6 percentage points higher than those reported by younger adults.

While his analysis didn't show cause, he told the Deseret News it was likely it reflected traits of that generation, which came of age during the so-called sexual revolution. Creation of medications like Viagra and loosening social mores likely contributed to the increase as well, he said.

Wang's new analysis found a somewhat different timeline. Like Wolfinger, she found women born in the 1940s and 1950s were more likely to cheat, but for men, the highest percentage was among those born in the 1930s and 1940s, she said.