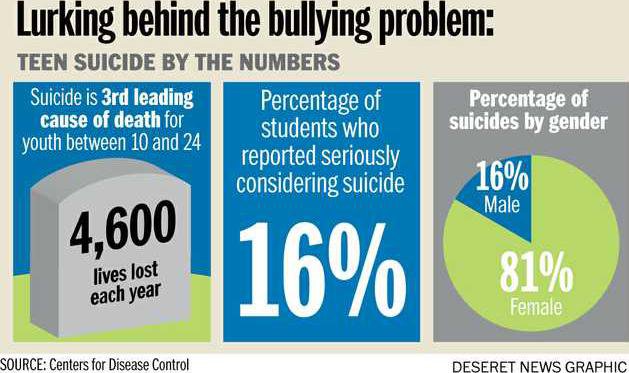

With suicide the third largest cause of death among teens, according to the Centers for Disease Control, the role of bullying in fomenting self-destructive thoughts has drawn increasing attention in recent years.

A recent survey conducted at Clemson University found that 16 percent of students between grades 3 and 12 reported being bullied often, between 2 and 3 times a month.

And many experts fear that the rapid rise of social media has made bullying and harassment among teens both easier and more damaging. In 2011 a Centers for Disease Control survey found that 22 percent of girls and 11 percent of boys had been bullied on social media in the past year.

Schools and cities around the country have begun looking at legal means to rein in bullying at school. Last week a southern California city council, following models set by two Wisconsin cities, tentatively voted to criminalize the bullying or harassment of school age kids. A final vote is slated for later this month.

Authorities in Carson, California, a city of 93,000 in Los Angeles County, hope the proposed law can reduce depression and teen suicide, as well as forestall episodes of school violence.

Carson’s proposed ordinance would make bullying a misdemeanor crime, but the arresting officer would be empowered to reduce the citation to an infraction, on par with a speeding ticket.

The city would also criminalize parental indifference. After parents have been warned regarding their child’s behavior, if the child bullies again within 90 days the parent is assumed to have “allowed or permitted” it and could face the same legal penalties.

No one doubts the good intentions of anti-bullying ordinances, but some skeptics fear that the proposed law’s noble goals mask serious constitutional issues.

UCLA law professor Eugene Volokh, for one, doubts that the Carson ordinance would stand up to constitutional scrutiny. The law could suppress constitutionally protected speech while granting too much authority to the arresting officer, he argued.

The core challenge for the Carson proposal, Volokh says, is that it appears to be “vague and over broad,” rendering it easily subject to abuse and very difficult to defend from constitutional challenge under the First Amendment.

Community support

Carson modeled its proposed law on similar efforts in a handful of other cities, including that of Milton, Wisconsin. In four years of enforcement, Milton has avoided legal challenge or even significant controversy by enforcing its law very cautiously, local authorities say.

Milton has a very strong anti-bullying push in the community, with parent and student groups focusing attention on the issue, Milton Police Chief Dan Layber said. The police department website has a bullying alert web form that allows anonymous reporting of incidents including the names of the bully and the bullied.

“We meet regularly and provide a lot of education to the schools,” Layber said. “We get a lot of publicity.”

Most bullying incidents are handled internally by the schools, with the threat of police involvement serving as a backdrop rather than a primary tool, said Jim Martin, the police officer assigned to Milton’s schools.

The first case that went to court under Milton’s law in 2010 involved a kid screaming in the face of another child, after repeated abuses and repeated warnings. He was fined $177 under the ordinance, pled guilty in court, and ultimately paid $100. His parents attended the court proceedings.

But unlike Carson’s proposed rule, Milton does not hold parents directly accountable. If fines are imposed on kids, parents usually will help make sure they get paid, Martin said. But if parents decline, the fine will remain on the child’s record until they get their first job or try to get a driver’s license.

A low profile

Martin is the one who first suggested the city adopt its anti-bullying ordinance after concluding he needed more flexible tools to discourage bullies.

The ordinance, he says, simply takes the existing harassment statutes, which would be a criminal misdemeanor charge if invoked, and translate them into a noncriminal “forfeiture.”

This allows the city to pursue cases that would technically be criminal under the harassment law, but are more properly addressed with a low profile.

The penalty could be a fine, but the judge has discretion to require a letter of apology of or some kind of community service. Martin has issued five or six citations a year since the ordinance was passed in 2010.

“Most of the kids stop after I warn them,” he said.

But most cases never come to that. Martin only engages the most severe cases, and draws a sharp distinction between the kind of behavior that requires intervention and the usual push and pull of the schoolyard.

Martin says he often has conversations with youth who complain about other kids spreading rumors behind their backs. “That’s called gossip,” he tells them, “and you just need to tell your own friends you don’t want to hear about it anymore.”

With this kind of restrained enforcement, Eugene Volokh is not surprised that Milton’s ordinance has survived four years without being shot down by the courts. It is too early to say if Carson would follow suit.

Vague and over broad?

As written, the Carson law certainly could reach well beyond where Jim Martin draws the line in Milton.

Supporters of the Carson ordinance say its legal grounds are based in state harassment law, Volokh notes, but he points out that California state law requires that the harasser actually “seriously alarm, annoy, or harass” the victim.

The Carson law's much broader and more vague language requires only that the harasser engage in behavior that “would cause a person to feel terrorized, frightened, intimidated, threatened, harassed or molested and which serves no legitimate purpose.”

It’s a subtle but critical distinction that puts enormous power in the hands of the authorities by removing the need for a victim to be “seriously” harmed.

Likewise, Volokh notes that Carson’s proposed law, unlike the state harassment law, attempts to regulate “hurtful, rude and mean” messages, reaching to social media and Web pages that make fun of people.

In describing cyberbullying, the proposed ordinance states that "it may include sending hurtful, rude and mean text messages; spreading rumors or lies about others by email or social networks; and creating websites, videos or social media profiles that embarrass, humiliate or make fun of others…."

Volokh worries that if any derogatory or mean-spirited communications could legally constitute harassment, local authorities will be empowered to decide when snark becomes a crime.

"This is not how our criminal law ought to work," he said.

Schools, cities reach for anti-bullying ordinances, but constitutionality in doubt