ATLANTA — Some get paid millions to try and solve the riddle facing the Michigan coaching staff at the Final Four this weekend.

How do you score against the Syracuse 2-3 zone defense? Lately, there seems to be no answer.

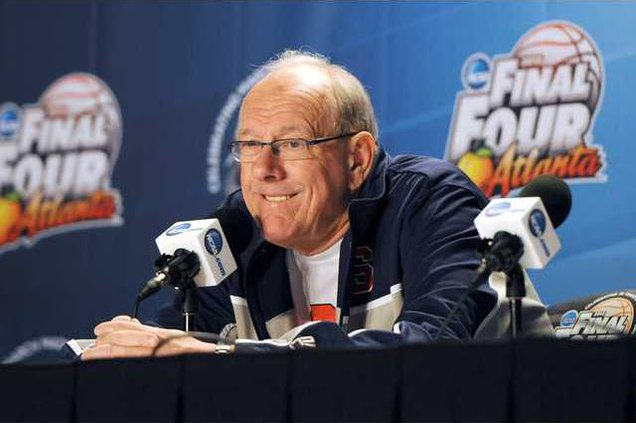

More than any single player, it’s the amoeba-like creation crafted by Jim Boeheim over the past 37 seasons and honed to near perfection over the last month that’s turning into the team’s trademark.

With hundreds of college basketball’s brightest minds in town for a coaching convention that runs in tandem with the Final Four, The Associated Press picked out a handful and asked them this simple question: Given a week to game plan, how would you try to pick apart Syracuse?

“A week to prepare?” said Steve Robinson, a longtime assistant for Roy Williams, who also had stints as a head coach at Tulsa and Florida State. “Some people haven’t been able to prepare for that and they’ve had all season.”

Take, for instance, Syracuse’s last opponent.

Last week in the regional final, Marquette’s Buzz Williams faced Boeheim’s defense for the seventh time since becoming head coach at the Big East school. The Golden Eagles scored 39 points on 12-for-53 shooting.

“We collectively tried everything we knew to try,” Williams said after that loss. “It is the zone, and it is the players in the zone.”

Not that he’s alone.

Syracuse is allowing 45 points a game and 27 percent shooting in the NCAA tournament, making some of the scoreboards look like vestiges from the pre-shot-clock era.

“The 2-3 zone is one of the most basic zones you face,” explains Miami’s Jim Larranaga, named Thursday as The Associated Press Coach of the Year. “What makes Syracuse’s zone is the players. They’re long, athletic and they cover a lot of ground. So, what appears to be an open shot is almost always going to be challenged by an outstanding athlete.”

Boeheim started with the 2-3 back when he got the job at Syracuse in 1976. He started using it more in 1996 when 6-foot-8 forward John Wallace brought the Orange just one win shy of the national title. Syracuse won it all in 2003 with Carmelo Anthony leading the way but it was Hakim “The Helicopter” Warrick — the 6-8 forward with the 7-foot wingspan — who swooped from the middle of the zone to the wing to block a last-second shot and save a three-point victory for the Orange.

“Here’s a ‘5” man coming out and blocking a shot in the corner,” Larranaga said. “Not many teams have players with that size and the athletic ability to make that kind of play.”

Syracuse played man sporadically over the ensuing years. But after giving up 50 second-half points playing that way in an exhibition loss to Division II LeMoyne in 2010, Boeheim went almost exclusively to zone. He hasn’t changed since.

“It has certainly withstood the test of time,” said Michigan coach John Beilein, who faces Syracuse and its zone Saturday in the national semifinals. “Jim continues to work at it and tweak it in different ways.”

Anyone expecting the defense to look like it would if drawn up on a greaseboard — two, evenly spaced guards up top and three evenly spaced big men down low — will not recognize this 2-3.

“They’re not just standing around giving up shots and hoping the other guy misses,” said John Rhodes, an assistant at Duquense.

To counter-attack, Rhodes and the rest of the coaches interviewed by AP said an offense must work the ball inside — first to the high post, hoping two defenders will collapse and create a mismatch elsewhere, then down deep on the baseline, almost behind the basket, an awkward spot from which to get to the hoop.

“The high post guy either has to turn and shoot if he’s open, or turn and look down to the baseline, or get the ball out to the wings,” Air Force coach Dave Pilipovich said.

Pilipovich said getting a man on the low post to set ball screens for the ballhandler — a counterintuitive notion against a zone because there’s not always someone to pick off — is also a must for breaking it down.

“You’ve got to try to outnumber them on the perimeter, three against two,” he said. “Problem is, they’re very good at sliding under screens so they can take that away from you.”

Indeed, it is Syracuse’s length — guard Michael Carter-Williams is 6-foot-6 and Brandon Triche is 6-4 — that makes the Orange so difficult to break down. Hard to see over them. Hard to pass around them. They’re averaging six blocks and 11 steals a game in the tournament, almost unfathomable numbers for a zone defense.

Coaches also talk a lot about dribbling into the middle of the defense to break it down, but because of their wingspan, it’s hard to dribble past them.

“He recruits to it,” Oregon coach Dana Altman said of Boeheim. “He’s got guards who are 6-5, 6-6. I have a feeling no matter what defense you put them in, they’d be pretty effective, because they’re so athletic.”

Chris Crutchfield, an assistant for Oklahoma, works for Lon Kruger, who is considered one of the top tacticians in the game.

“We talked about that before we left,” Crutchfield said. “I don’t know how you do it.”

One obvious problem, Crutchfield says, is that teams don’t see the zone all that much during the season, so they don’t practice for it. Then, when they do — well, it’s hard to make it look like Syracuse’s zone.

“You don’t have the athletes they have to simulate it,” he said. “You can practice against it, you can talk about putting the ball in certain places, but you can’t simulate that. So, now, the gaps that you’ve seen in practice, you’re not going to see them because they cover up all those gaps. It’s really unbelievable.”

One team that did have some success this season was Louisville. The Cardinals went 2-1 against Syracuse in 2013. In their 78-61 win in the Big East tournament, they shot 40 percent — not great, but still better than any of Boeheim’s last seven opponents.

Rick Pitino’s strategy was to set up two men opposite each other on the high post and throw the ball into one of them. The other post man cuts to the hoop. The man with the ball then either looks to that cutter, or if that man is covered, throws to a guard who should be spotted up open in the opposite corner.

“If Louisville plays Syracuse in the championship game, you can look for the same strategy,” Larranaga said. “That’s not necessarily saying they’ll shoot it as well as the last time they played.”

In reality, all coaches agree that the only way to truly loosen up a zone is to make shots from the outside.

Michigan has a great candidate to do that — the AP’s Player of the Year, Trey Burke, who averages nearly 19 points a game and shoots nearly 40 percent from 3-point range.

Asked how he would game plan for Burke, Boeheim, not surprisingly, didn’t sound all that concerned.

“I don’t pay attention to matchups,” he said. “It’s teams. Teams play.”

Few play the team game better than Syracuse is playing it right now.

“It’s full time in terms of the way they play,” Robinson said. “They’ve established their niche and how they play, and it’s effective and it works for him.”

Syracuse becoming known for its zone defense

NCAA Tournament