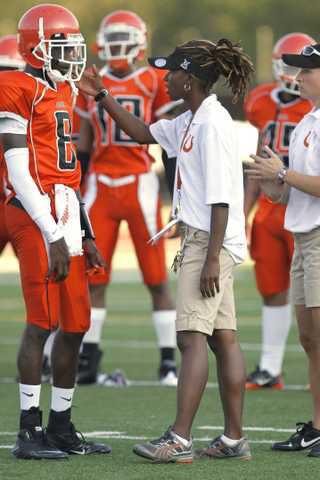

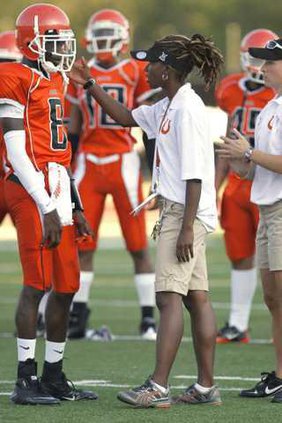

WASHINGTON (AP) — Natalie Randolph is a novelty no more — at least not in these halls. She’s something even better: A winner.

Twenty months ago, the national media swarmed into a classroom at Coolidge High School to observe a curiosity — a press conference to announce the hiring of a female high school varsity head football coach, believed to be only one in the country. The special guest was the mayor, who happened to be running for re-election.

Last Friday, students flocked to the school’s gymnasium for a celebration. Randolph has led the Colts to an 8-2 record and a berth in the most puff-your-chest-out, school-pride game of them all in the nation’s capital — the Turkey Bowl city championship on Thanksgiving Day. The pep rally’s noteworthy guest was longtime NFL receiver and Coolidge graduate Jerry Porter, visiting from his California home.

“I got word Coolidge was in the Turkey Bowl and I was like, ‘Yeah, I’ve got to come check it out,’” Porter said. “It’s huge. Because when I was here, we didn’t have very many winning seasons. We mostly watched the Turkey Bowl.”

And the fact that Randolph is a woman is so yesterday. She could be the Man (or Woman) from Mars if it meant being on the field for that 11 a.m. Thanksgiving kickoff. When Coolidge faces Dunbar (8-3) on Thursday — a rematch of a game won by Dunbar in overtime earlier this month — the last thing on Randolph’s mind will be the game’s sociological impact.

“People have kind of forgotten about it, so that makes it nice,” Randolph told The Associated Press in an interview in one of the school’s locker rooms. “But it’s always been about football. It’s never been about gender or whatever, at least not for me.

“Other people, I don’t care what they think, but it’s always been about the kids.”

School officials adamantly denied that Randolph’s hiring was a publicity stunt. She was more than qualified, they pointed out — a city native, a former University of Virginia track star, a receiver for six years with the D.C. Divas of the National Women’s Football Association, an assistant coach for three years for the football team at rival H.D. Woodson.

The only questions seemed to be would the players respect her and could she win.

For a while, it didn’t look good. She lost her first five games.

“Last year, I think, was overwhelming,” said Shedrick Young, the Colts’ defensive coordinator last season. “It was overwhelming for all of us. That first game was something we never experienced, with all the cameras and stuff on the field, and media. We’re not used to that, so when it calmed down and the media wasn’t around, that’s when the team started to jell. We started to play well.”

The fifth loss came after the Colts allowed a 99-yard winning touchdown drive in the final minute. Afterward, Randolph gave a long, blistering speech to her players — a defining moment in the season.

“The kids kind of realized they don’t want that feeling anymore,” Young said. “After that, they believed in what we were doing. Instead of individual accolades, they played for each other. ... We didn’t baby ‘em anymore. She’s probably got the worst mouth on the field sometimes. She’ll let ‘em know.”

The Colts won their next four and backed into the playoffs, finishing with a 4-7 record. The momentum carried into this season, when Randolph was able to coach her first practice and first game without the distraction of all those cameras and reporters. She never much cared for all the attention anyway.

“I’m not one to be all out in the open,” she said. “I’m not a person that really enjoys being out in the public eye, and when I have something to do, I want to do that. I don’t want to be bothered.”

What she wants to do is teach and coach.

Athletic director Keino Wilson said the overall GPA of the team is up from 2.65 last year to 3.1. Randolph juggles her classes — biology and environmental science — with the sometimes unique challenges of coaching in a city where schools always seems to be facing logistical and financial hurdles.

Randolph’s coaching staff was down to four earlier this season because of a new citywide process for approving assistants. The logjam is taking months to sort out. Young has to watch practices from the stands while waiting for his paperwork to clear, which means Randolph herself had to take charge of the defense.

“I had to call the defensive plays for, like, seven games,” she said. “It’s more of a collaborative effort now. I’m glad, especially now that we’re in these big games.”

After the pep rally, the Colts went to the field to practice, and they kept on going even when it became so dark that it was difficult to see the ball. The field has lights, but they are set to a timer. Finally, they came on at 5:30 p.m. to cheers from some of the players.

When practice finally ended, the Colts retreated to the locker room, thinking about their place in Coolidge history. Not as players for a female coach, but as players with a chance to win the city’s biggest prize.

“Everybody had that demeanor of ‘She’s a girl coach, she’s a female,’” said senior receiver Dayon Pratt, an East Carolina recruit. “Now this year, it’s a ‘dedicated coach’ — and we’re going to the Turkey Bowl.”

Female prep football coach has team in DC title game