Each week we’ll take a step back into the history of Great Bend through the eyes of reporters past. We’ll reacquaint you with what went into creating the Great Bend of today, and do our best to update you on what “the rest of the story” turned out to be.

It was this week in 1910 that the 6th International Congress of Esperantists was held in Washington, D.C. It would be the first of only three events hosted by the United States in over the past century, and because of this the interest in Esperanto trended up for a short period.

Esperanto, we learned, is a constructed language designed to be easy for anyone to learn, and intended to increase communication and understanding between all people of the world. It only has 16 grammatical rules that have no exceptions, and there are groups all over the world that speak and write in Esperanto. Every year, a convention is held in a different spot on the globe, except this year, for what has become the accepted reason for all cancellations of annual fun of any sort.

A description of the event appeared in the journal Science, on Sept. 16, 1910, describing the event as, “a gathering of persons from many nations, as diverse as possible in their national characteristics and tongues, but alike in the one respect, that they spoke the artificial auxiliary language, Esperanto, and consequently had a common medium by means of which to exchange ideas when they met, either socially or in convention assembled.”

The writer noted that the members there were from nations from all over the world, and most did not know the native tongues of their fellows, but communicated with ease in Esperanto.

“The thoughts and emotions of these men of other climes and tongues, which had been before as a sealed book, were at last approachable at first hand, and my mental horizon seemed to broaden and the way to a new world-view lay invitingly open before me.”

If your interest is piqued, and you wonder if you might be able to learn Esperanto, we found a website with a series of self-paced lessons you can check out online at https://lernu.net/en/kurso/nakamura.

BriberyIn Great Bend, interest was consumed by two unfolding events, one of regional interest and the other of local interest. In Oklahoma, a lawyer, J.F. McMurray, was subject to a Congressional inquiry, on charges of bribery.

McMurray, an attorney of McAlester, Okla., advised the 600 members of the Chocktaw and Chickasaw nations to enter into land contracts with him, and through a member of the Republican committee offered a bribe to

Senator Thomas B. Gore to remove certain legislation pending in Congress to speed up the transfer and facilitate the payment of $3,000,000 to McMurray.

“The money was to represent “attorney’s fees” of 10 per cent on $30,000,000 which was to be secured from a New York syndicate for 450,000 acres of coal and asphalt land now owned by the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians in this state.”

Under congressional scrutiny, it came out that parents had signed their own children’s names to contracts, some of whom were still babies.

According to one Choctaw plaintiff, “We were led to believe the contracts were a good thing,” he said. “We considered that McMurray knew better than our congressmen and senators how to go about selling the land. We believed that by signing the contracts we would realize quicker on our claims against the government. That’s the way I and the children signed up.”

The issue was tied up in the courts for about two years. It didn’t end favorably for the plaintiffs. For a summary of what happened, check out the Facebook page, “Choctaw Woman- Mela Comes Home.”

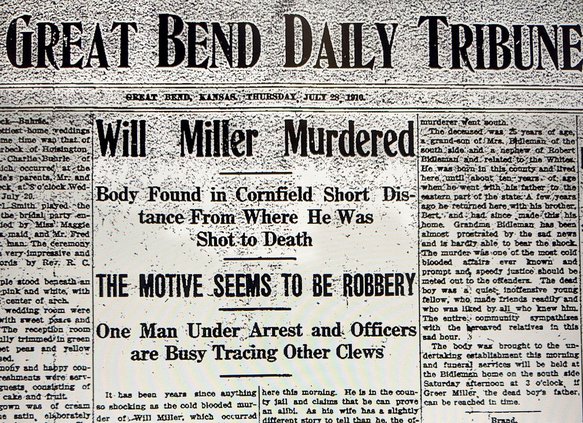

Locally, authorities were combing the countryside in search of the person who murdered a well-like farmer, William Miller, who farmed ground south of Great Bend, who was 25 years old, born in the area, and a grandson of “Grandma Bidleman” who was also well liked in the area.

“Some person or persons went to Miller’s tent last night on the Dick farm, three and one-half miles south of town, and shot him through the head, death occurring instantly. There is no clue to the guilty party but as they apparently took Miller’s four horses and wagon it does not seem possible that they can escape. Word has been telegraphed in every direction and their capture seems certain,” the report stated.

Miller had been to his grandmother’s the night before, and arranged to meet up with his brother, Bert Miller, the next morning to fix fence.

“When Bert arrived this morning he found a light burning and the floor of the tent and bed covered with blood. He made an ineffectual search for the body of his brother, fearing ill play but only succeeded in finding that the horses and wagon were gone.”

A search ensued, and a farmer, William Hiss, discovered the Miller in the corn field near the tent.

At first, a Geo Hantz, a farm hand and horse trader, was suspected. But, his alibi was good, and a person in possession of the stolen wagon and horses was apprehended near Hutchinson. That person, C. W. Culver was captured in Sylvia. On his person was also Miller’s watch and a check for $65 dollars signed by Miller. It was noted earlier that Miller rarely carried cash and paid for goods by check most of the time. The man tried to get away when he was approached, and tore up the check.

A few days later, “while he was being taken to Hutchinson from Sylvia by auto the officers told him 20 auto loads of friends of the dead man had started for Sylvia to get him and when the auto broke down, he asked for something with which he could end his own life as he wanted to see that his family got his insurance. He was later safely deposited in the Hutchinson jail. He refused to tell where he lived. This was assumed to be an admission of guilt by the press. But, there was a second set of footprints where Miller had been left after he was murdered.

A few days later, Culver gave his confession -- but not to murder. He told of witnessing two people driving the wagon the night of the murder, who abruptly stopped and jumped out of the rig and ran off. He waited awhile to see if they would come back, and debated bringing it into Great Bend, or not. He concluded if he brought it back, he’d be arrested for horse stealing, so instead he went south, sold one of the teams and got a check for $65 (the one signed by Miller himself), and then tried to cash it at the bank in Sylvia, he said. When he saw the man looking at the wagon, he figured he was caught for stealing the rig and horses, and attempted to escape.

Days later, authorities learned Culver was actually an alias. The man’s name was Henri Logan, and his family was from Ottawa. Culver, it turns out, was the name of an acquaintance of his who lived and worked in Wellington and who resembled him in appearance. That Culver was head of the Wellington Gambrill’s Grocery. He had visited Great Bend the day before the murder. It is unknown but probable that Logan had seen him in town. This Culver, however, had an airtight alibi for the night the murder occurred, having already returned home to Wellington on the train.

Evidence was mounting against Logan, and his wife was hopeful his brothers might step up to offer financial assistance so he could hire a lawyer. They did not come through.

In the end, Logan was transported to Barton County for trial. He was not lynched as he feared. He was forced to represent himself, and he was his only witness, save for some depositions as to good character from friends in Ottawa. He was found guilty of second degree murder after the jury spent 12 hours deliberating.

“Locally the verdict is not satisfying. The majority of people on the streets say it should have been a verdict of first degree murder or acquittal. A prominent attorney here declares that Kansas ought to have a Matteawan (a New York State hospital one of the nation’s most famous institutions for the “furiously mad”) and proper defense would have landed Logan there. But everyone believes in the man’s guilt. It is only in regard to the manner in which the deed was done, that there is a difference of opinion.”

Unfortunately, there were no public defenders in 1910. In fact, California was the first state to establish the practice in 1913, and other states slowly began adopting the model. It would be 1963 before the Supreme Court “declared it an “obvious truth” that an indigent person cannot receive a fair trial against the “machinery” of law enforcement unless a lawyer is provided to him at no cost,” according to the website SixthAmendment.org.