Prognosticators for the 2023 hard red winter wheat crop yield in Kansas have been digging into the archives lately, as they put their best guesses in.

Even with a 2-3 inch rain last week, the crop is still suffering from drought effects the further west one travels across the state. If the rain continues, expectations are that the current drought – now in its third year – is still wreaking havoc on the state’s signature commodity and the question is, how bad can it be?

In his preview address to participants in the Wheat Quality Council’s 65th Annual Wheat Tour last week, Aaron Harries, Kansas Wheat’s vice president of research and operations warned that the bar could be pretty low.

“The big question is: will the crop be under 200 million bushels or over?” Harries said. “The harvest in Kansas hasn’t been below 200 million since 1963.”

A bleak forecast

Following the Tour’s wrap-up Thursday, the projection for the state was 178 million bushels. The participants’ three-day average calculated from fields to be harvested was 30 bushels per acre.

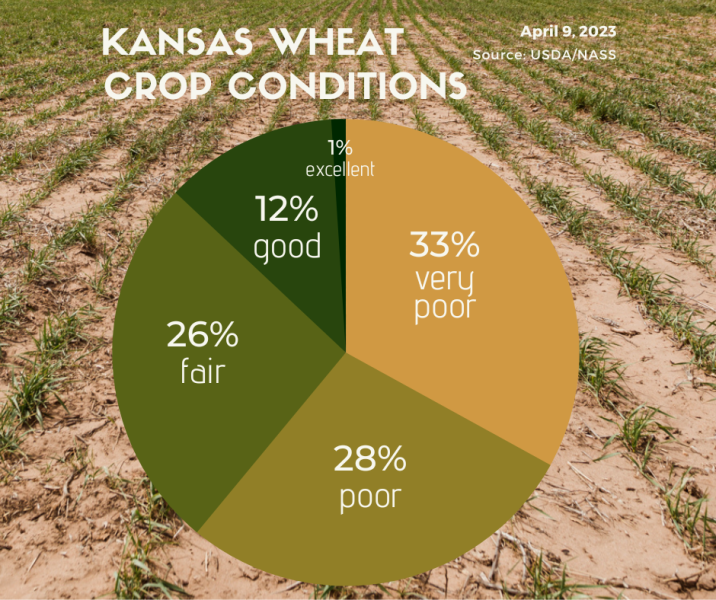

While an estimated 8.1 million acres were planted in the fall, the tour projected abandonment could reach as high as 26.7%. May 1’s wheat condition report by the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service had the Kansas crop at 68% poor to very poor. That’s a sobering figure, Harries said. NASS had predicted a higher crop total at 191 million bushels, with a yield average at 29 bushels per acre and abandonment at 18.5%.

The next closest measuring stick is 1996, when the crop suffered from late freezes rather than dry weather. In the end, 25.4% of the planted crop was abandoned.

It was worse in 1989, he said, when 28% of acres never made it to harvest. Last year it was 9.6% while the average year is closer to 5%.

A bit of moisture last September caused some farmers to plant early, taking a risk on late-season disease. That crop emerged in the fall, unlike the traditional October-planted wheat that didn’t have enough moisture to emerge until late spring.

Getting ready

For seven decades, the WQC has drawn attendees from throughout the United States and beyond, catering to every link in the “grain chain” beyond the producer.

Most of the attendees, however, have never seen a wheat field, much less than know how to measure what it is they see.

Interest in being a part of the #WheatTour23 has been outstanding, according to Dave Green, Wheat Quality Council executive vice president. “The most we’ve ever registered was 88, and we’re right at 106.”

The tour is just as much about educating the next generation of agricultural employees as it is about collecting data. The participants are skilled in their own areas of expertise.

“They’re smart; they’re college-educated; they’re ready to go,” Green said. “But they’ve never been in a wheat field. And so, this is an opportunity for companies and other agencies to get people out, a chance to actually walk the fields. See what’s involved with yield and production, and ask questions that help them do their jobs better when they get back to their office.”

The first night, tour organizers taught participants how to measure a field and use NASS equations to estimate potential wheat yield. Harries, along with Romulo Lollato, Kansas State Extension wheat and forage specialist, told participants what they may see in the fields.

Lollato walked the participants through the agronomics of the wheat crop. He said this year’s wheat crop faced outstanding drought conditions across the two-thirds of the state that grows the majority of wheat, with the southwest and south-central regions bearing most of the pain. One positive from this drought is the dryness has limited fungal disease pressure. There’s not enough moisture to sustain rust. The irony is, as tour participants gathered in Manhattan on May 15, a steady rain was falling over most of the state.

“The rains are welcome to sustain yield potential,” Lollato said. But at this point, the crop has developed heads, and farmers are just worried about protecting that potential, and hopefully, they can get a crop to harvest.

The first day

People from 22 U.S. states plus Mexico, Canada and Colombia, packed into 27 cars on six routes between Manhattan and Colby on Tuesday, stopping at wheat fields every 15-20 miles along the routes.

Many tour participants had never stepped foot in a wheat field before and had only seen these Kansas plains from the window seat of passing airplane. These are the millers, bakers, food processors and traders who buy the wheat that Kansas farmers grow. If these fields make it to harvest, the resulting crop will go into breads, but also a number of other food items and restaurants.

Tuesday’s cars of wheat tour scouts made 318 stops at wheat fields across north-central, central and northwest Kansas, and into southern counties in Nebraska. The calculated yield from all cars was 29.8 bushels per acre, which was nearly 10 bushels lower than the yield of 39.5 bushels per acre from the same routes in 2022.

Every tour participant makes yield calculations at each stop based on three different area samplings per field. These individual estimates are averaged with the rest of their route mates, and eventually added to a formula that produces a final yield estimate for the areas along the routes. While yields tend to be the spotlight of the Wheat Quality Tour, the real benefit is the ability to network among the “grain chain.”

Lon Frahm and family hosted the Tuesday evening group discussion and dinner at his sixth-generation farm, Frahm Farmland in Thomas County. He offered tour participants tours of his modern family farm operation.

Drought and variability were the main topics for the first day’s wrap-up of the wheat tour. Stand establishment was spotty last fall, and the crop is thin and short. There were several abandoned fields between Manhattan and Colby. Fields began to turn more brown as groups went farther west. Manhattan and Salina had a large fraction of freeze-damaged fields on Tuesday’s trip west.

Wheat fields showed really dry conditions and really cold temperatures which had a detrimental effect. Participants did not report much disease and insects because of drought. There were a few spots with brown wheat mites but rain drowned them and suppressed populations. While there were some areas with decent wheat, the poorer wheat outnumbered the good. Ample producers may have called crop adjusters due to wheat being emerged throughout the spring that leads to very low yield potential.

The second day

Participants toured the state from Colby to Wichita along six routes on Wednesday, winding up back in Manhattan. The calculated yield from all cars was 27.5 bushels per acre.

The final day

On Thursday, yields in areas between Wichita and Manhattan were better than what participants had seen earlier on the tour, improving as they moved north, averaging 44.1 bushels per acre.

For fields that have not yet headed out, scouts used an early season formula model to calculate the potential yield of the fields. The model uses an average head weight based on 2013-2022 Kansas wheat objective yield data. For the fields that had already headed, attendees were able to use a late-season formula to calculate yields, based on number of wheat heads, number of spikelets and kernels per spikelet. Tour scouts didn’t see much disease pressure this year with the drought conditions.

These fields are still 3-6 weeks from harvest. A lot can happen during that time to affect final yields and production.

Kansas Wheat’s Marsha Boswell contributed to this report.