Each week we’ll take a step back into the history of Great Bend through the eyes of reporters past. We’ll reacquaint you with what went into creating the Great Bend of today, and do our best to update you on what “the rest of the story” turned out to be.

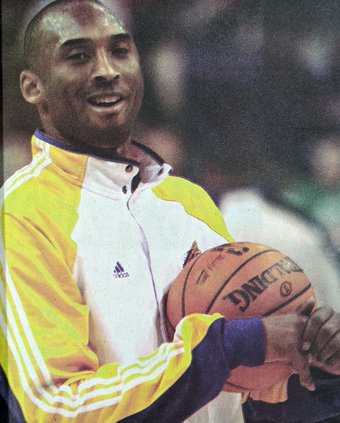

It was just 10 years ago on April 2, 2010, that NBA superstar Kobe Bryant signed a three-year contract extension with the Los Angeles Lakers worth a cool $87 million. The team also signed 7-foot center Pau Gasol to an extension, albeit a slightly smaller one, achieving its two main objectives for the year.

“We were able to accomplish those goals, helping to keep the core of this team intact for the foreseeable future and in turn help to ensure the franchise’s continued success over the years to come,” general manager Mitch Kupchak said.

Bryant retired at the end of the 2015-2016 season at the age of 35. Over his career that spanned two decades he had many awards: two Olympic gold medals, five championship rings, 17 All-Star selections, an 81-point game that ranks as the second-best in NBA history and more than 32,000 points.

On January 26, 2020, the world was shocked to learn of Bryant’s death at age 41. He died, along with his 13-year-old daughter Gianna and seven others, in a helicopter crash in Calabasas, California. Reports stated they were on their way to a basketball game where he would coach his daughter’s team.

Walk a mile

And it was 10 years ago that Great Bend’s Family Crisis Center coaxed several area men for the first time to “Walk a Mile in her Shoes,” around Jack Kilby Square.

The men wore red stilettos as they made their way around the square in varying degrees of awkwardness. It was part of the International Men’s March to Stop Race, Sexual Assault and Gender Violence. Each team of four men paid a $200 fee, and received a t-shirt and a pizza coupon as a gift for their participation. The event itself occurred on April 17, but The Great Bend Tribune did its part to promote the event ahead of time. Men posed for promotional photos at Jack Kilby Square on April Fool’s Day in 2010.

The event had its highs and lows as far as participation goes over the years. This year, every organization in the country is trying to determine what sort of events are even possible amidst stay-at-home orders of various levels of severity, and many events have been postponed indefinitely, in hopes things will be better in a few months. The Family Crisis Center’s Facebook page currently is promoting an Aug. 28 event called “Red Shoes and Bunco Too,” a ladies night out event. However, online registration has been closed down for the time being, but expected to be up again in August.

Flashback to 1918

Speaking of stay-at-home orders, which have been issued effective Monday, March 30, due to the current COVID-19 crisis the country faces, we offer this little detour as we revisit the March 1, 2018 Out of the Morgue entry. The topic of that week, the onset of another worldwide pandemic which started here in Kansas:

On March 4, 1918, Private Albert Mitchell, a mess cook at Funston Army Camp, Ft. Riley, reported sick. For the past month, soldiers had been coming down with varying flu-like symptoms. A week later, at least 100 soldiers at Funston were in the hospital, and the disease had spread to Queens, New York, (according to “Spanish Flu strikes during World War 1,” Internet wayback machine). Days later, it was over 500. Mitchell, it was determined, had contracted a new strain of flu. It was the first recorded case of Spanish flu, marking the start of the first wave of a worldwide pandemic that would kill 50-100 million people.

Censorship is the reason today we refer to the disease as the Spanish flu, rather than the Funston Flu or the Kansas Flu. According to a report on EurekAlert! The Global Source for Science News, “The name “Spanish flu” came from the fact that Spain was not a partner in World War I and its press was freer to report details of the pandemic than press in combatant countries who did not want to reveal information about deaths and sickness to enemies.”

That bears out with wire reports in the Great Bend Tribune from this week in 1918. In the March 4, 1918 edition, attention focused on the health of soldiers deployed to Europe. No epidemics reported there, and whatever illness soldiers there might be suffering were purely American made, which we assume was meant to be reassuring.

“The crest of the sick rate was reached the first week in February with 6 percent from which was an immediate drop. The average is about 5 percent, of which percentage scarcely half are bed cases.”

The first wave was reportedly mild, compared to the second wave. According to History.com, “...a second, highly contagious wave of influenza appeared with a vengeance in the fall of that same year. Victims died within hours or days of developing symptoms, their skin turning blue and their lungs filling with fluid that caused them to suffocate. In just one year, 1918, the average life expectancy in America plummeted by a dozen years.”

It has been noted that the Spanish flu “struck down many previously healthy, young people—a group normally resistant to this type of infectious illness—including a number of World War I servicemen.

In fact, more U.S. soldiers died from the 1918 flu than were killed in battle during the war.”

The term “social distancing” is specific to our time. In 1918, there wasn’t any such term, and the concept apparently hadn’t occurred yet.

In another March 4 report, “Kissing is popular; That Old-time “out-in-the-moonlight” stuff has passed at Camp Funston,” a clue to one way the Spanish flu was passed is provided.

“The war has revolutionized kissing, at least at Camp Funston. For if there is anything a Funston Sammee likes better than a kiss, it’s a couple, or three, or a half dozen kisses.”

The report went on. “Kissing is just a matter-of-fact business down here, and the 300-foot platform of the Union Pacific station at this camp is the Kissin’ist place in this section of the country.” The description of girlfriends, mothers, aunts, sisters and second cousins vying for kisses at the platform followed.

“Now it’s hard to tell how he does it, but the Funston Sammee has a way of clinging to the side of a coach and at the same time putting both arms around the girl’s neck and planting a loud, healthy kiss on her waiting lips. Maybe he “stands on air,” but anyway, he sure gets results. Scores of such scenes are staged at the arrival and departure of each train.”

Since World War 1, doctors have learned as much about the flu and how it’s transmitted. A day prior to symptoms occurring, and for days after the sickness passes, the sick can pass the virus through with respiratory fluids, through coughing, breathing, sharing food, and kissing.

As we all hunker down and prepare to stay home and reduce the spread of our century’s version of the “1918 H1N1 pandemic” as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control refer to the flu today, stay safe by practicing good hygiene and observing a social distance of at least six-feet but preferably 10-feet, and remember, “this too shall pass.”