Each week we’ll take a step back into the history of Great Bend through the eyes of reporters past. We’ll reacquaint you with what went into creating the Great Bend of today, and do our best to update you on what “the rest of the story” turned out to be.

Today is 140th anniversary of the date generally recognized as the start of the “Exodus of 1879,” when 6,000 southern blacks led by Benjamin “Pap” Singleton began the migration to Kansas, Missouri, Indiana and Illinois seeking a chance to be the masters of their own destiny and escape racial violence in the South.

Already by that time, it is estimated around 50,000 “Exodusters” had migrated to form colonies in these Midwest states. A large group from Tennessee settled in Topeka, and the Dunlap colony was established near the borders of Morris and Lyon Counties. Others were more independent, and sought land under the Homestead Act, and settled in parts of Barton County. Further west, the Nicodemus settlement was established in 1877 by black settlers from Kentucky, independent of any Singleton efforts, and exists yet today.

We looked at three Great Bend newspapers that were in publication in 1879, The Inland Tribune, The Great Bend Register, and The Arkansas Valley Democrat, to learn if this historic movement was on the local radar. It was not, but settlement of “the Indian question” was. How to assimilate and/or remove to reservations the Indian population was the question that was eventually answered through military might in the 1880s.

Each newspaper had a different editorial personality, which shines through in the positions taken by each concerning the treatment of Indians, and where the responsibility for their plight lay.

Readers of the Inland Tribune would have read:

“The settlement of the Indian question is one which has for years annoyed and puzzled the brains of many of the thinking men of this country, and for years it has been the policy of the government to look upon these untutored sons of the forest as wayward children, who have just sense enough to be doing wrong all the time, but not sufficiently intelligent to be responsible for their errors. Our notion is that the peace policy with these people is all wrong. The government has no business treating with them, and always the first to break the treaty. The policy was wrong in its inception. They were, are yet, and always will be a set of savages, standing in the way of advancing civilization...”

And it just get more critical and mean spirited from there.

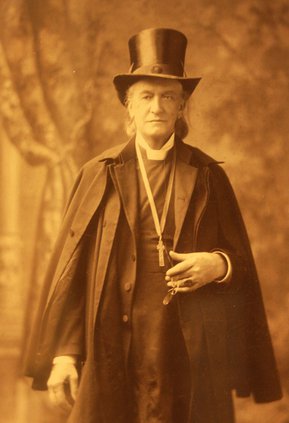

Readers of the Arkansas Democrat would have read a half-page history of relations between the U.S. and the Indians in a feature written by Bishop H. B. Whipple, the first Episcopal bishop of Minnesota and an advocate for Native Americans.

“The Cheyennes were among the most friendly of the Indians of the plains. They were a brave, noble type of red men. After gold was discovered in California, the United States made a treaty for the right of way across the Indian country, in which the Cheyennes joined,” he wrote. He went on to state, “The treaty was faithfully observed by the Indians. Emigrants crossed the plains in safety, singly, in companies, in ox teams and on foot. Gold was discovered in Colorado; the whites flocked to the new El Dorado. The rights of the Indians were forgotten.”

His recounting of the numerous slights by the U.S. Army against the Cheyenne was thorough.

“We have fallen on evil times-- the rulers, the people, the press, the army, all describe our Indian system as a wicked system of blunders and crimes. Why need we go on this blind, stupid path of sin where we must reap exactly that which we sow? Why cannot the press, the army, the people strike hands together and send up such a plea for justice that the nation may no longer bear the sin and shame of this iniquity?”

Such divided outlooks are familiar in the wake of modern controversies. Perhaps now is a good time to look more closely than ever at the events of 140 years ago and consider the lessons learned then.

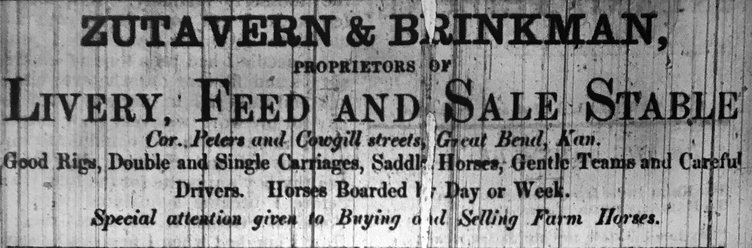

The Great Bend Register had less philosophical writing, and more local news. This week, the Register proposed the city vote a bond to pay G. L. Brinkman’s judgment against the city. Brinkman was one of the proprietors of the Great Bend Livery, Feed and Sale Stable. He was seeking to be compensated for the sidewalk he built up to the depot several years earlier.

“We are tired of the continual wrangle over Mr. Brinkman’s claim against the city. It is unpleasant and breeds personalities and bitterness between citizens, which is against good public policy,” the editor wrote. “We know it may be said that the amount of Mr. Brinkman’s judgment is much larger than in equity it should be, and that the city should not be held liable. But probably the easiest and cheapest way out of the trouble is to put off until tomorrow what you don’t wish to do today.”

The Register also carried a guest editorial calling for compulsory education in Kansas.

“The people are taxed to build an furnish these school houses; they are also taxed to pay a teacher for at least six months in each year; this for the benefit of every person of school age within the district, yet by actual showing one-half derive no benefit whatever for their effort.”

In a related report,

“W. S. Trent closed his five months school in Dist. No. 22 on last Friday, the 27th, ult., and is now enjoying a three weeks vacation, after which he intends taking up a three months term at the same place. He says he has had a very pleasant school this winter.”

Compulsory education in Kansas became the law in 1874, according to the Kansas State Department of Education. “In 1874 the Legislature passed a compulsory school attendance law for children ages 8-14. By 1885, the state wanted to provide more than an elementary education to a greater percentage of its children. County high schools were authorized and supported in the state.”