Each week we’ll take a step back into the history of Great Bend through the eyes of reporters past. We’ll reacquaint you with what went into creating the Great Bend of today, and do our best to update you on what “the rest of the story” turned out to be.

First, a correction. Last week, we looked at the life of filmmaker Oscar Micheaux. A typographical error was made, so let us set the record straight. Micheaux was born in 1884, not 1864. Thank you to the diligent reader who caught the error and brought it to our attention, noting, “It’s good to see that Great Bend is keeping Oscar’s memory alive.”

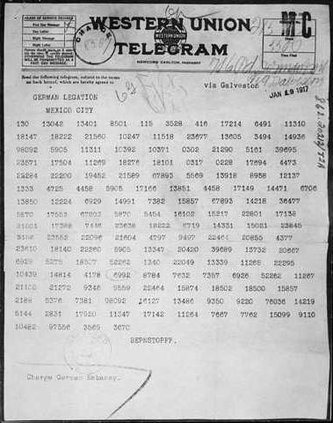

Zimmerman telegram released

This week, the United States began seriously considering what part it would play in the ongoing war in Europe when the plain text of what has become known as the Zimmermann telegram was released to the public on March 1.

That intercepted communication revealed a German plot to unite with Mexico and Japan against the United States should it not remain neutral following the German’s announcement of unrestricted submarine warfare. Up until then, the Republicans in Congress had been against empowering the president to arm ships and “use other instrumentalities” to deal with Germany. Following the release of the telegram, they began to reach across the aisle and assured Democrats they would stand directly behind President Wilson, it was reported.

A report from Mexico City indicated Mexico intended to remain neutral in the war, and the German effort was in vain.

Meanwhile, an Amsterdam report from a German newspaper indicated the Germans were ready to fight should America begin arming neutral transport ships.

“There is no doubt the arming of American merchantmen will mean a fight between submarine and American vessels, which necessarily will produce a state of war.” Things were really beginning to heat up.

The next day, it was reported students at Kansas State Agricultural college in Manhattan were already considering how they could officer troops should the country go to war.

Sooy drilling starts

Meanwhile, readers were alerted in a large advertisement that Saturday afternoon, March 3, the Cheyenne Oil & Gas Co. will start their first well.

“You and your friends are cordially invited to come out and see actual drilling of an oil well. Come and bring your friends.”

A.A. Frederick was listed as the “fiscal agent,” and subscriptions of the capital stock for the company were being solicited for $10 each.

The Saturday morning paper carried this report, “Opening of oil well.”

“In case some needed parts of the machinery, a brake band, and something else of that nature, can be fixed today, the drilling of Barton county’s test oil well will start this afternoon or evening. And when the work starts it never stops without cause. If it gets started today the visitors to the well tomorrow will see the machinery in operation.”

But, because of the failure to get some needed parts to the site and impending weather, it didn’t get started until Monday, March 5.

“Several carloads of people went out to the fields Saturday afternoon to see the first oil drill for a long time bore into mother earth to find what is under the stretch of land called the Cheyenne Bottoms, but they were all disappointed. By Monday, drillers were back at it, working away, and the public was still cordially invited to come out and watch.

Eventually, there was success. According to the book, “Barton County, Golden Heartland of Kansas,” written by historian Marge Harrington and published in 1996 by The Great Bend Tribune, this well started in 1917 is known as the Sooy, and these efforts touched off a drilling race within the county. Businessmen put our feelers to attract drillers to this area. Drilling stopped initially at 300 feet, as the drillers were combatting some pretty frigid weather.

“A New York company then came in to complete the well at 3,500 feet. But then that company made a deal with another New York firm, and a Wichita individual, who finally completed the well six years later,” Harrington wrote. While this well was never a big producer, the novelty attracted visitors, and this spurred some entrepreneurs to bring in support services for workers and tourists alike. According to Harrington, “One Great Bend taxi driver knew a good thing when he saw it. He constructed a hamburger stand at the site and made about as much as the oil well owners.” The well was ultimately abandoned, and it would be another 15 years before the Silica field was tapped, becoming one of the three major Barton County pools.

MoPac offices completed

Reported on Friday, March 2, 1917, the offices of the new Missouri Pacific Depot in Hoisington were just completed at an expense of $4,000, making it “one of the most complete modern and up-to-date railroad offices in western Kansas. It coincided with the completion of the Vaniman building, at an expense of $5,000, described as “another one of Hoisington’s modern new structures containing several fine office rooms above while the basement is occupied by the Hoisington Drug Co.”

These developments, along with repairs to other buildings pointed to great building prospects for Hoisington in the spring. “Plans for many new buildings are already drawn up for the opening of spring.”