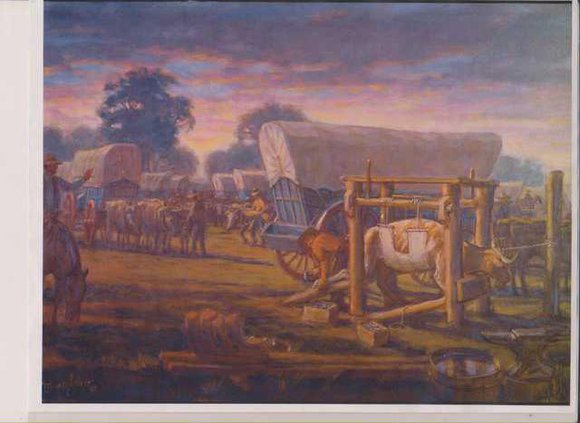

Editor’s Note: Local historian David Clapsaddle writes about aspects about the Santa Fe Trail. The Santa Fe Trail eventually included Fort Larned and Pawnee County. “Old Dan and His Traveling Companions,” profiles oxen on the Santa Fe Trail.

By David K. Clapsaddle

Regardless of conventional wisdom, drivers were often encouraged to spare the whip, especially during the latter part of the period when American traffic on the Santa Fe Trail was monopolized by huge freighting firms.

The handling of oxen was stipulated in great detail by written regulations issued to personnel employed by the various firms.

Tom Cranmer who compiled a set of such regulations wrote, “I would therefore, most emphatically denounce the practice of beating oxen under all circumstances.”

However, such was not the case with the Mexican drives.

James Mead recalled, “The drivers were known as “bull whackers” or “mule skinners,” mostly semi-Indian half civilized, faithful, brown skinned, with hair of jet hanging on their shoulders, wielding lashes with such skill as to cut a rattlesnake’s head off at 20 feet, or cut through the hide of an refractory ox.”

Perhaps more effective then the whip were the voice commands of the driver.

Walking near the head of the wheelers, he spoke well recognized commands the oxen learned quickly to obey.

Originally, “gee-up,” meant to move up. In time, the command became “giddyap.”

Gregg wrote that a simple “hep,” was the command to move forward.

“Gee,” was the command to turn right; “haw,” was the command to turn left. “Whoa,” originally “ho,” was the command to stop.

With regard to other voice commands, Cranmer wrote, “No loud cursing, swearing, or frightening of cattle should ever be allowed in the corral.

In the settled part of the country, calves at an early age would be yoked together and exercised daily. Small training yokes were used and sometimes sliding (adjustable) yokes were employed to accommodate the animal’s growth. The calves were allowed to grow to full maturity at age three before they were castrated. This allowed the animal to mature into a strong animal before the neutering process rendered him more docile.

Freighters on the frontier did not have the luxury of time to train oxen. Rather, they often purchased mature but unbroken (green) steers at the trail heads and immediately put them into service. Unbroken oxen would be yoked and stationed between the experienced teams.

Thus snared, they had no choice in spite of their protestation by means of backing and bawling but to proceed in step with their broken brothers.

As the caravan proceeded, the green oxen remained yoked together day and night for some two weeks. Thus, they were forced not only to work together but to eat and sleep together on a 24-hour basis. Subsequently, they performed as broke oxen in an amicable manner.

The author in recent years had the opportunity to talk with a Flint Hills rancher who imported cattle from Mexico. He observed, from time to time, a pair of steers which appeared to be inseparable; they were together constantly. The rancher went on to say that upon closer inspection, he found that the animals were shod, a sure sign of their draft animal status in Mexico.

Thus, it would appear that the yoking of oxen produced a reciprocation by which the animals maintained a steadfast relationship, working or not.

Tom Cranmer’s regulations stipulated, “See that all hands temporarily mark their cattle the first time they unyoke, so they may be able to recognize them afterwards.

Howard recalled, “One driver tied bits of black cloth to the tails of his team.”

(To Be Continued)

Bull whackers employ colorful language