Editor’s Note: Local historian David Clapsaddle writes about aspects on the Santa Fe Trail. This series profiles how Santa Fe Trail freight, passengers and mail shifted from the overland trail to railways.

By David K. Clapsaddle

During the first four decades of its 59-year tenure, the Santa Fe Trail was repeatedly shortened as its eastern terminus was moved westward from its original Missouri River landing at Franklin upstream to Independence, Westport Landing, both in Missouri, and finally to Leavenworth, Kansas, the last of the river ports from which merchandise, and beginning in 1850, mail and passengers, were dispatched to Santa Fe.

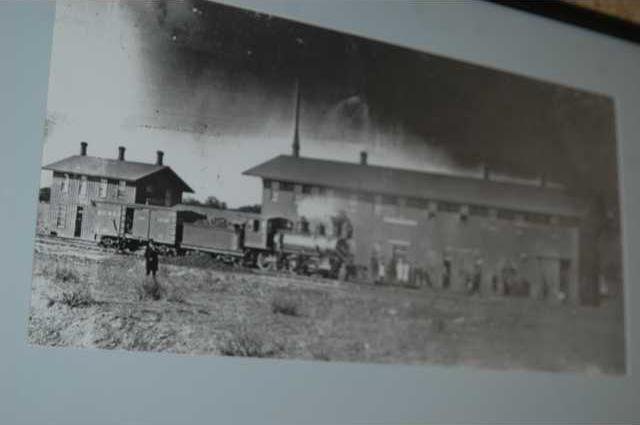

In 1863, the Union Pacific Railway Company, Eastern Division (UP) began laying tracks westward from Wyandotte, Kansas.

In late June of 1866, the tracks reached Junction City, Kansas. The small town near Fort Riley became, at once, the railhead for the UP and the eastern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail.

Freight, passengers, and mail formerly dispatched from the Kansas City area down the Santa Fe Trail via Council Grove were thence shipped by rail to Junction City and transported by wagon and stage on the Fort Riley-Fort Larned Road to Walnut Creek. Consequently, overland traffic on the Santa Fe Trail east of Walnut Creek came to a halt.

Corresponding to the arrival of the railroad at Junction City, the postal service contracted with Barlow, Sanderson and Company to deliver mail on a tri-weekly schedule from Junction City to Santa Fe.

Barlow, Sanderson established seven stations on the 120-mile stretch from Fort Riley to Fort Zarah at Walnut Creek — Chapman’s Creek, Abilene, Salina, Pritchard’s (Spring Creek), Fort Ellsworth, Well’s Ranch at Plum Creek, and Fort Zarah.

Later, the Cow Creek station originally operated by the Kansas State Company was reopened.

The new stage line experienced little difficulty with Indians thanks to the protection afforded by the company of the 37th U.S. Infantry stationed at Fort Ellsworth under the command of Lt. Frank Baldwin.

Baldwin assigned four or five men to each of the stations between the Smoky Hill and Walnut Creek. In addition, the stagecoaches were provided escort with troopers either riding atop the stages or alongside in wagons.

Fort Ellsworth, renamed Fort Harker in November 1866, was moved about one mile to the northeast of its original location in January or 1867. Corresponding to the time of Fort Harker’s relocation, the town site of Ellsworth was ill advisedly established west of the Fort Ellsworth site on the flood plain of the Smoky Hill River.

In April 1867 Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock marched onto the Plains of Kansas with 1,400 troops: infantry, cavalry, and artillery.

Accompanying the expedition was engineer Lt. M.R. Brown whose precise notes provide a wealth of detailed information with regard to the itinerary followed on the Fort Riley-Fort Larned Road.

Leaving Fort Riley, the expedition crossed Chapman’s Creek 13 miles west of the post. Proceeding 13 miles further along the north bank of the Smoky Hill, the column crossed Mud Creek at Abilene.

Brown noted that in the center of the little city was a town of prairie dogs.

Beyond Abilene the expedition crossed the Solomon and Saline forks on a portable pontoon bridge built on canvas boats by Brown’s engineering squad. At the Solomon crossing, nine miles beyond Abilene, the expedition was joined by Henry M. Stanley, a correspondent for several eastern publications.

Stanley’s journalistic observations provide a human and often humorous perspective of the expedition, complementing the accurate, yet tedious, accounts complied by Lieutenant Brown.

Santa Fe Trail begins to shorten

Trails to Rails Part 1