Editor’s Note: Local historian David Clapsaddle writes about aspects on the Santa Fe Trail. This series profiles how Santa Fe Trail freight, passengers and mail shifted from the overland trail to railways.

By DAVID K. CLAPSADDLE

Having no official name, the road to Fort Lyon was known by several designations. Captain W. H. Penrose, commanding officer at Fort Lyon, referred to the road as the stage route to Cheyenne Wells.

Luke Cahill, a state company employee and former first sergeant in the Fifth Infantry at Fort Lyon, called the road “the trail between Lyon and Wallace.”

At a later date, the road was commonly known as the Fort Wallace-Fort Lyon Road. Whatever the name, this road eliminated another significant section of the Santa Fe Trail, the stretch running westward from Fort Dodge to Fort Lyon.

The northern end of the line was construed to be any of three locations — Sheridan, the railhead which received passengers, mail, and freight from the east; Fort Wallace, 12 miles southwest of Sheridan, which housed the post office established in 1866; or Pond Creek Station.

There the Southern Overland initiated a daily stage service to Santa Fe effective July 1, 1868. Actually, the stages ran only six days a week, departing each end of the line Monday through Saturday.

Between Pond Creek and Fort Lyon, the stage company established six stations at varying intervals, each named for a water source — Cheyenne Wells, Sand Creek (Big Sandy), Rush Creek, Kiowa Springs, Well No. 1, and Well No. 2. Beyond Cheyenne Wells, originally a BOD station 36 miles from Pond Creek Station, the threat of Indian attack was ever imminent.

As early as August 30, 1868, Captain Penrose at Fort Lyon reported: “the country between here and the Denver stage road, the Smoky Hill and also between here and Fort Dodge is over run with hostile Indians, every precaution is taken to protect the Stages, the Trails, and the settlers in my vicinity as is possible to do without cavalry. While Penrose referred to the Indians in generic terms, it appears that the majority of the raiders were Cheyennes and, to a lesser extent, Arapahos and Kiowas.

At Sand Creek, 14 miles from Cheyenne Wells, Indians attacked the Big Sandy station on Sept. 19. However, troops dispatched from Fort Lyon four days previously were able to repulse the raiders without any losses. One Indian was reported killed and another wounded in the exchange.

The Rush Creek Station, 15 miles beyond Sand Creek, never experienced Indian problems, but Kiowa Springs, 22 miles to the southwest, was not so fortunate. This station, kept by a Mr. Stickney, was attacked on Aug. 25, 1868, but the Indians were driven off with no losses on either side.

At Well No. 2, only 12 miles from Kiowa Springs, a coach returned to the station on August 24 after proceeding only about one mile toward Fort Lyon. Being warned by a courier that Indians were in pursuit, the conductor turned the coach and raced back to the station. Waiting until darkness, the coach slipped away from the station and quietly made his way to Fort Lyon, arriving 12 ½ hours behind schedule.

Well No. 1 was 15 miles beyond Well No. 2 and seven miles from Fort Lyon. On Aug. 28, 1868, a party of 25 to 30 Indians surrounded the station.

After observing the stage company employees were prepared for the attack, the Indians left without incident.

At Well No. 1, Lydia Spencer Lane and her husband, William, stayed overnight in 1869 while en route to the railhead at Sheridan.

Mrs. Lane’s brief sketch of the property might well serve as a prototype of the stations on the Fort Wallace-Fort Lyon Road — “We stayed all night at the small board shanty used as a mail-station, occupying the state apartment, I suppose, for the walls were papered with illustrations from various pictorials. I had a suspicion the pictures were put there more to keep out the wind — of which there is an undue allowance of kind and quality in Colorado — than to embellish the room. A bright and cheery little place it was, with windows that commanded a view of the country for miles in every direction.”

Following the Battle of Beecher’s Island in September 1868, northwest of Fort Wallace and the Oct. 9 capture of Clara Blinn and her 2-year old son Willie east of Fort Lyon, the Cheyennes and their southern plains allies moved south of the Arkansas to winter in the Washita River Valley.

Then traffic on the Fort Wallace-Fort Lyon Road returned to a peaceful flow.

Nevertheless, the Southern Overland officials armed their employees at company expense and on Dec. 5 requested Captain Penrose to assign troops to each of the stations between Fort Lyon and Cheyenne Wells. At that time only 24 men were available for duty at For Lyon.

Consequently Penrose dispatched four men at Fort Lyon to escort stages southward and assigned three men at Fort Lyon to escort stages northward.

Penrose informed his superiors — “This arrangement does not seem to meet the approval of Mr. Barnum, (Superintendent of the Southern Overland Mail and Express Company) but is the best I can make.”

During the winter of 1868 to 1869, the majority of the southern plains tribes were subdued by General Phil Sheridan’s winter campaign and forced onto reservations in Indian Territory. The Cheyenne Dog Soldiers were an exception, and they were slow to surrender their freedom.

In the spring of 1869, a contingency of Cheyennes, comprised mostly of Dog Soldiers, moved north to the Republican River area in Northwest Kansas where they resumed their depredations on the Fort Wallace-Fort Lyon Road.

At Sheridan, they ran off several hundred mules in May 1869, and the following month they raided a caravan near Fort Lyon.

Throughout the summer, numerous bands of Indians were reported along the Fort Wallace-Fort Lyon Road. Fortunately, no lives were lost in any of the encounters.

Trouble of a different sort occurred during the same period. While a coach was en route to Well No. 2 from Fort Lyon, a driver named Huggins killed another stage company employee named Taylor. Because both men had been drinking, Huggins was not held responsible for Taylor’s death. He was relieved of his driving duties and assigned to Well No. 2 as a stock tender.

Not finding the new duties to his liking, Huggins left the company’s employment. Shortly thereafter, the station was closed.

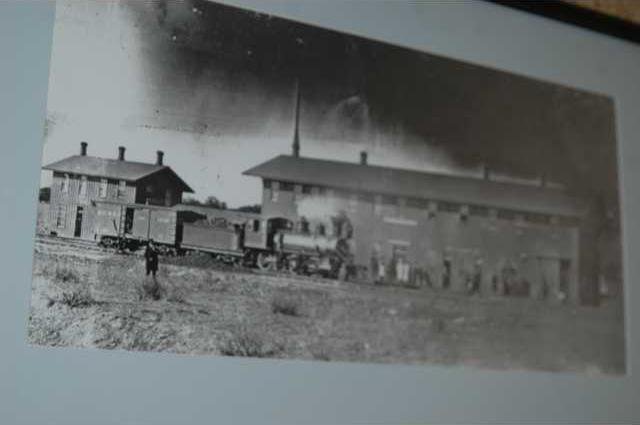

By this time the town of Sheridan had grown to a population of 2,000, swelled by the lawless element common to end-of-track towns.

A reporter for The Topeka Commonwealth, described the situation in the issue of August 4, 1869 — “The scum of creation have there congregated and assumed control of municipal and social affairs. Gamblers, pickpockets, thieves, prostitutes and representatives of every other class of the world’s people, who are ranked among the vicious, have taken possession of the town and reign supreme. Civil authorities are laughed at and disregarded, and crimes are rampant and predominant.”

Regardless of such observations, a sizable proportion of the population was comprised of respectable personnel associated with giant forwarding companies.

Employing clerks by the score, these firms operated mammoth wholesale operations disbursing goods to New Mexico by way of freight caravans operated by New Mexico merchants who found a ready market for their wool at the Sheridan railhead.

(To Be Continued)

Santa Fes Dodge to Lyons stretch eliminated

Santa Fe Trails to Rails Part 7