The Shafer Art Gallery will host an opening reception for the CUNA Mutual RS Art & Science Encounter, “The Geometry of Beauty” by Bradford Hanson-Smith from 6:30-8 p.m. on Friday, in the Shafer Gallery. A CUNA Mutual RS Art & Science Encounters Family Day will be held from 10 a.m. to noon on Saturday, in the Shafer Gallery. Families are invited to learn how to make art with folding techniques by Hanson-Smith at this free family event.

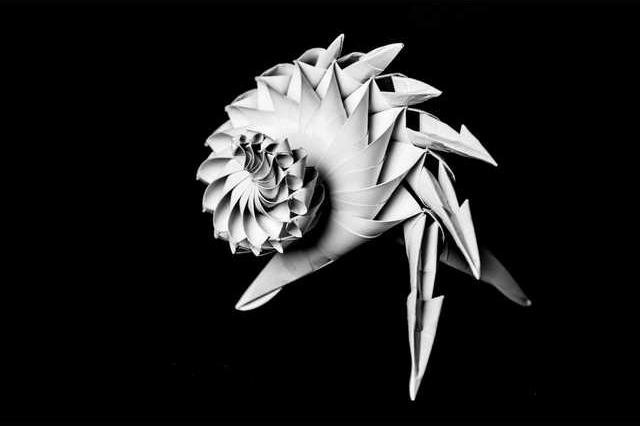

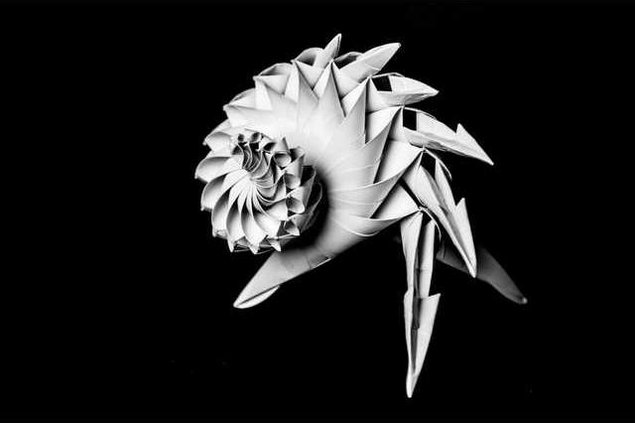

The gallery will be filled with hundreds of Hanson-Smith’s creations and will show the process of his exploration of the circle.

“My interest is to find out what the circle is, what it generates and what it reveals,” Hanson-Smith said. “To give people the idea that the results are not the important thing, it’s the process. I want you to discover what you find, whatever you are doing you need to value the process and not the product.”

Hanson-Smith works in the three-dimensional realm of art through folding circles, most of which are paper plates. These plates are folded into an equilateral triangular grid matrix that is then refined and combined in multiples to create forms.

He has taken this approach and uses it to help teach geometry and math through a hands-on experience which he calls Wholemovement. Wholemovement is about making art and math but it is also about pedagogy. Hanson-Smith’s belief is that traditional forms of teaching math have not been as effective as they could be and there is a better way of engaging a student’s mind.

“It is difficult teaching mathematics because we are using archaic language and concepts from 2,000 years ago. It’s not that they are wrong, but our experiences today are different,” Hanson-Smith said. “When you think of any language on this planet it is continually evolving, almost daily; math is one of those languages that does not change.”

Hanson-Smith began his Wholemovement journey more than 25 years ago. Before folding circles, Hanson-Smith was a sculptor. One day, a friend informed him of an opportunity to take a class on Buckminster Fuller’s geometry taught by Hazel Archer who worked alongside Fuller. At first Hanson-Smith was not interested but decided to give it a chance.

“The first class I went to, it changed my life,” Hanson-Smith said.

Archer recommended Hanson-Smith read a book by Fuller titled “Synergetics,” which he struggled to understand. After studying 2D and 3D patterns for five years and returning to “Synergetics” he found having a hands-on experience with Fuller’s concepts finally helped him understand “Synergetics”.

Hanson-Smith learned how Fuller instructed students to fold paper plates as he lectured to provide a physical experience. With further research Hanson-Smith realized everything can be modeled by folding circles.

Soon after he began folding circles Hanson-Smith was given the opportunity to teach art for a week at a school. He thought that instead of doing traditional art projects students could fold circles. Through this experience with the kids, he began to see the potential the activity could have on students understanding math.

“When you fold a circle in half there is a tremendous amount of information within that first fold if we observe what we do, but we don’t. We have a preconditioned idea of what we do, we are going to fold it in half,” he said. “We are not looking to see what it is we have done or how it was done.”

Hanson-Smith believes that through a hands-on approach students can retain knowledge greater than listening and thinking about the concepts.

This strategy helped many obtain a better understanding and a growing interest in math, geometry and natural form including Scott Beahm, Gallery Associate at the Shafer Gallery.

“In grad school, I was seeing more and more of the formal qualities that I wanted to work with in art and they seemed mathematical; I didn’t know how to get into that,” Beahm said. “Then I came across his work and it was like learning about it through the back door, through hands-on work of simple patterns that build upon themselves. I was just so turned off to the normal approach to math that it really appealed to me that someone was using other ideas and talking about it in a different way.”

As time progressed, Beahm found himself leaning more toward pure math with greater understanding than before. Beahm hopes that others who found themselves in a similar struggle with math can gain appreciation and knowledge from Hanson-Smith.

Shafer Art Gallery to host opening reception for CUNA Mutual RS Art & Science Encounter, The Geomet