One-fourth of Great Bend USD 428 students missed 17 or more days of school in 2022, Assistant Superintendent John Popp told the school board Monday. That’s 699 of 2,789 students.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on state assessment scores and exacerbated the problem of chronic absenteeism, administrators said. The impact of the pandemic on schools is statewide and Great Bend was not exempt.

“What we’ve lost in the pandemic will take us years and years to recover from but we believe that we have the structures in place,” Popp said.

Assistant Superintendent Tricia Reiser said students who were kindergartners when the pandemic started are third graders now.

“They still haven’t caught up,” she said. “Our students who were first graders during COVID are now fourth graders and they are now at pre-COVID; they’ve caught up.” At that age, learning needs to be hands-on and includes behavior, she said. However, “We’re making progress,” Reiser stressed.

Administrators looked at student achievement before and after COVID-19 for all students and for four subgroups – Hispanic students, English language learners, special education students, and students eligible for free or reduced-price meals.

“Some of our subgroups have been impacted more than others. It’s an equity issue; we want to make sure that we’re meeting the needs of all of our kids,” Reiser said.

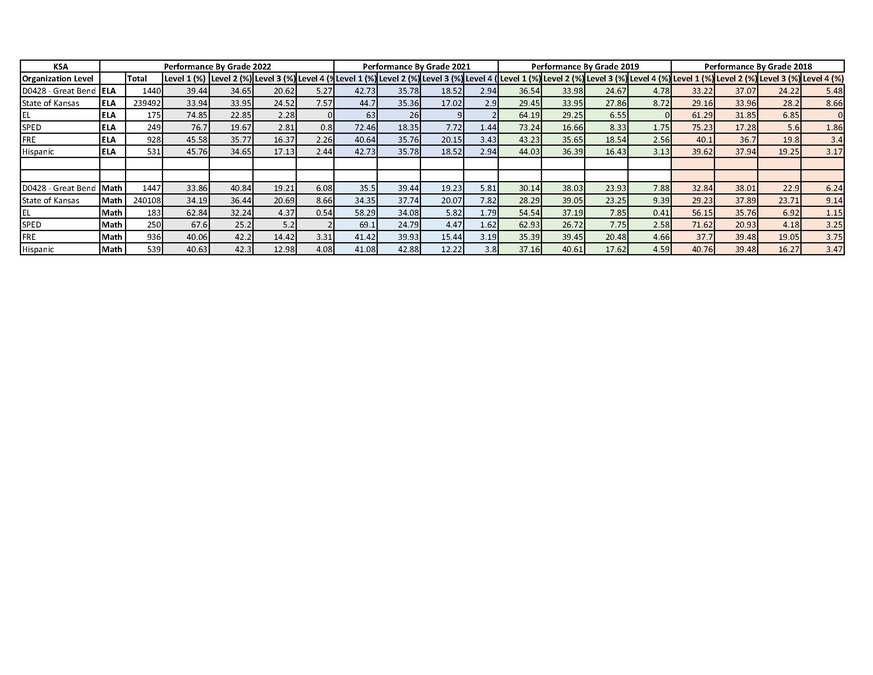

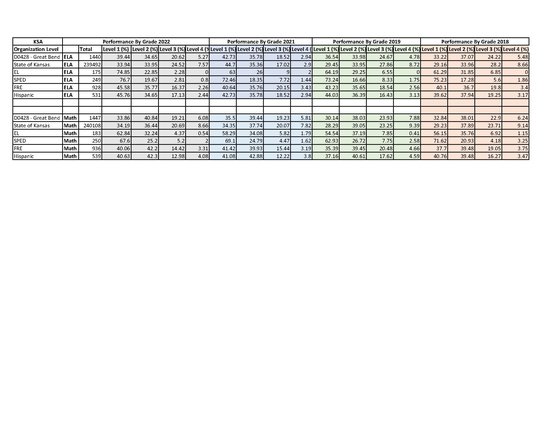

State assessments

Popp said state assessment scores place students in one of four levels for English language arts and for math.

Level one is the lowest proficiency and level four is the highest.

“You can see if you go back to 2018 that we had (33.22%) of our students in level one versus immediately post-pandemic; we’ve got 42.73% in level one in 2021, and then a year out from the pandemic (2022) 39.44%. That’s a lot of kids in level one.”

Statewide and locally, some of the subgroups especially “have been really hit by the pandemic and are struggling to recover,” Popp said. For example, 64% of English language learners were in level one prior to the pandemic and last year that number was 74.85%.

Math scores were slightly better but also show the level one group rose from 33% pre-COVID to 62.84% post-COVID for English language learners.

Reiser said Great Bend’s state assessment scores were improving prior to the pandemic. USD 428 was projected to score above the state average in 2020, but state assessment tests were not given. In 2021, “the data shows that that didn’t happen. We were really impacted. We want to get back to that trajectory for sure.”

A rigorous test

That doesn’t mean that 42% of our students are failing, Popp said. “Our state assessment is extremely rigorous.”

While the educators don’t want to see kids in level one, each level can also be split into “high” and “low,” Superintendent Khris Thexton said.

“You can see on the high level one’s, we’re not that far from jumping over into level two. When they jump from level one to level two, they go from a predicted ACT score of 16 to 18,” Thexton said.

“A high level two is correlated to a 21 on ACT,” Popp said. “That is college admission all the way, so that just shows how rigorous the state assessments are. It takes a pretty significant amount of knowledge to be able to get a 21 on the ACT.

“I would be hard-pressed to say that somebody that has a level two isn’t ready for college. So what we really want to see is these students that are on the high side of level one move into the level two on the state assessment,” he said.

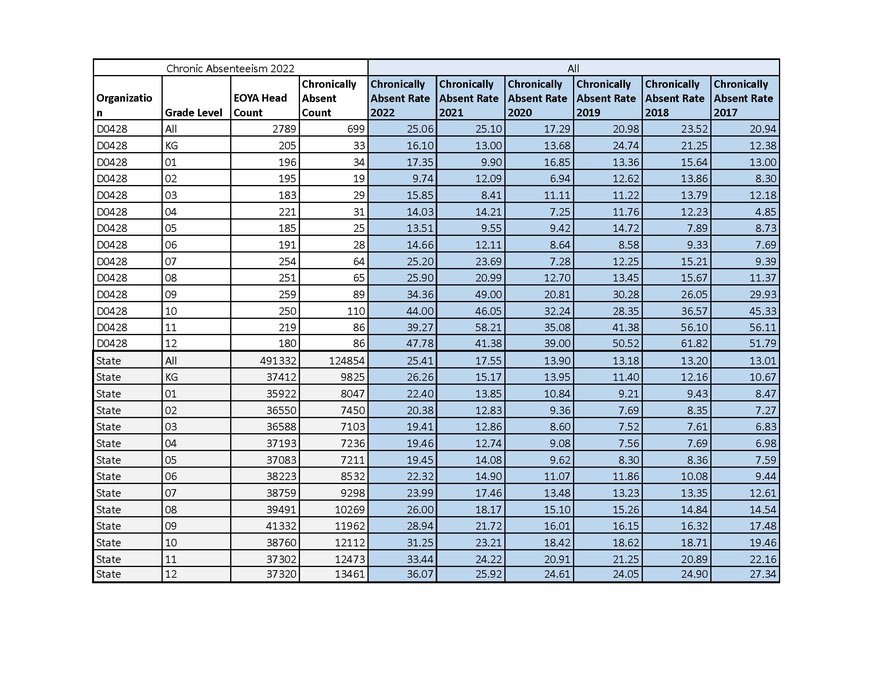

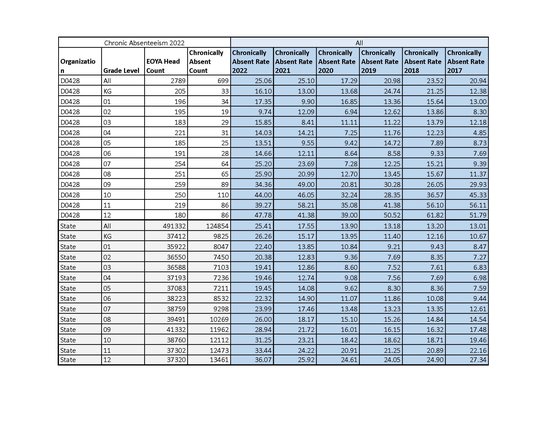

Chronic absenteeism

Popp said the state rate for “chronically absent” students across all age groups rose from 13% in 2017 to 25.4% in 2022. For high school seniors – the group with the highest level of chronic absenteeism – the rate rose from 27.3% to over 36%.

Locally, overall absenteeism went from 21% in 2017 to 25% in 2022. The rate for seniors here has been as high as 62% in 2018 and as low as 39% in 2020, after steps were taken pre-pandemic to reduce absenteeism.

Reiser said the pandemic is a root cause of much of the district’s current absenteeism.

Chronic absenteeism among Hispanic students tripled after COVID-19, she said.

Addressing the issues

The Kansas MTSS (Multi-Tiered System of Support) has been in place for several years, Popp said, and its structure will help schools recover.

“The nice thing is, we were on a nice trajectory with the MTSS process (before) the pandemic,” Thexton said. “We’re back into re-setting our MTSS.” That involves teaching the strategies to teachers who weren’t there and helping those who were familiar with the process to catch up again.

Reiser said part of the MTSS “reboot” has been to bring in experts in the teaching of math, reading and early childhood education.

“Another thing that we’ve been working on is teacher clarity,” Popp said. Teachers are taught to really understand the standards and what students need to know in order to move on to the next grade level.

This is different from the days of No Child Left Behind, where teachers “taught to the test,” he said.

“You have to teach the standards and then the questions are written around that concept,” Popp said. The questions won’t be ones the students have seen before.

Addressing absenteeism will also help.

“We know if a student is in school we can teach them,” Reiser said.

“You can’t teach them if they aren’t there,” Popp agreed.

Family engagement coordinators, hired in response to the pandemic, are helping. The district is stressing the importance of attendance. Showing up is also a skill that will benefit the students later in life, Thexton said.