Sara-Jane Smallwood had made her way to the top: a bachelor’s degree in Indian American studies, a master’s in public policy from Indiana University and a job on the Hill, working as a policy analyst for her U.S. senator.

But Smallwood came from the bottom: a small town in Southeastern Oklahoma where more than 60 percent of the population lives below poverty. Her high school class of 35 people didn't hold a 10-year reunion, because several class members had died, and many were in and out of prison.

But even though hers was an anomalous story of success, she speaks of her hometown with love and pride. And in 2011, Smallwood — the descendant of a long line of influential Choctaw tribal leaders and the daughter of two school teachers — decided that of all the hard work she saw at the top, very little was reaching the bottom.

“I think what’s brought me back home is that I got frustrated with so many smart people working for the federal government who are dedicated, but it’s hard to understand the grassroots level,” Smallwood says.

Smallwood is now the coordinator in the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma for a new national anti-poverty initiative the Obama administration is calling Promise Zones. The idea is that communities across the country that are designated as Promise Zones will have help to cut through the bureaucratic red tape that can make it difficult to access already available federal funding.

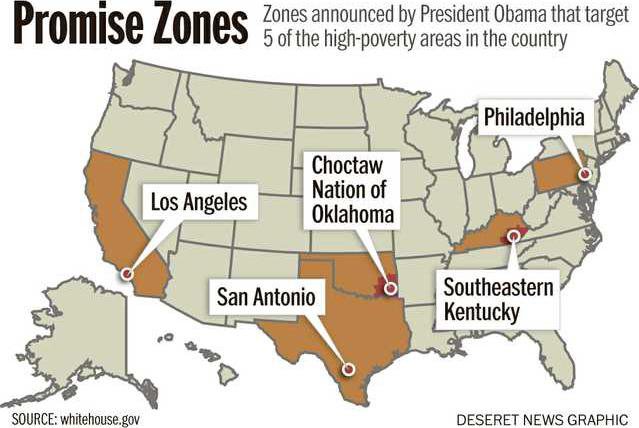

The Promise Zone initiative doesn't have any dollar amount tacked to it, or award funding to chosen communities. Instead, it's an initiative to get things going at a grassroots level, Smallwood says. Of the 20 forthcoming Promise Zones, Obama has announced the location of five: Philadelphia, San Antonio, Los Angeles, Southeastern Kentucky and the Choctaw Nation. In Philadelphia, officials are using the designation to partner with a local college to provide job training. And in San Antonio, officials hope improving street lighting and demolishing abandoned buildings will boost public safety.

"There are communities in this country where no matter how hard you work, it’s virtually impossible to get ahead,” Obama said in his 2013 State of the Union address. Poverty, Obama said, should not be determined by place of birth.

But the idea isn't without its critics.

“We have a huge welfare system in place that is federally funded," says Rachel Sheffield, a poverty researcher for the Heritage Foundation. "It would be better to focus on our current welfare system rather than adding to it with another government approach.”

A nation in need

Life in the Choctaw Nation has been characterized as bleak because poverty is rampant. On average, one in five people living in the Choctaw Nation live under the poverty line, which means more than 50,000 people live on less than $12,000 a year. And in some communities in the Choctaw Nation, one in every two people live below that line. Some counties in Choctaw Nation experience a high school dropout rate of 14 percent — more than twice the national average.

A recent analysis by the New York Times found that Southeastern Oklahoma is one of the most difficult places to live in the country. Measuring things like median income, college education rates and unemployment, the Choctaw Nation fares worse than the national average in every category. One of the most striking disparities was that people in the Choctaw Nation have an average life expectancy of 74 years, almost six years shorter than the national average. And 41 percent of the population is obese, a staggering difference from the national average at 27.7 percent.

Of the five announced Promise Zones, the Choctaw Nation is the largest geographic area, covering more than 10,000 square miles, including most of 13 counties. The lack of infrastructure in the area makes it especially difficult for people living there. Smallwood says that it can take two hours to travel to the nearest grocery store.

For all its challenges, Smallwood says Southeastern Oklahoma is one of the most beautiful parts of the country with miles of open farmland and tall timber canopies the highways on either side. Leaders of the Choctaw Nation are hopeful that becoming a Promise Zone may turn things around. The Choctaw Nation itself is the largest employer in the state, and the tribal government wants to partner with universities and local vocation schools to expand education.

Area leaders hope to use Promise Zone funding to expand the summer school program, which focuses on helping kids up to the third grade who are falling behind, and improve roads and other infrastructure. They're also pushing a bill to get tax credits for businesses that operate inside Promise Zones.

How much promise?

The idea behind Promise Zones is not a new one. Often called “place-based” initiatives, policies that target select pockets of high poverty are as old as Roosevelt’s Tennessee Valley Authority program, meant to revitalize rural areas during the Great Depression. Since then, ZIP code-targeted programs have been common, like the Appalachian Region Commission in the 1960s or George H.W. Bush’s Empowerment Zones.

Place-based policies are born, at least partially, out of the fact that in many areas poverty clusters and perpetuates. On top of that, poor people may not have the money or job-network to relocate, said Mark Partridge, an economic development professor at Ohio State University.

Partridge says the results of past place-based initiatives have been mixed, and little evaluation measures were in place. To be sure, Partridge said the Promise Zone effort is “very, very modest” because it lacks any backing from Congress and no actual dollars are attached. “This is basically an effort by a president who knows he can’t get anything through Congress and he wants to do something anyhow,” Partridge said.

The selection criteria for awarding the designation remain largely vague and has generated controversy.

The Los Angeles Promise Zone, for example, is made up of only a few, dense urban neighborhoods, and the boundaries of the Promise Zone doesn’t include the poorest communities in L.A. The L.A. Times reported that neighborhoods left out of the zone have a “poverty rate 21 percent higher than communities within the Promise zone,” with some communities up to 39 percent higher.

Smallwood said that because there is no direct funding attached to the Promise Zone designation, she’s not sure if the Choctaw Nation’s long-term plans will play out, especially because the designation will only last 10 years. Critics also say that programs like Promise Zones can create regions of dependency and that the selection process is easily politicized.

But the Choctaw Nation is hopeful the Promise Zone designation will help. And Partridge says past programs, even in ones with funding available that weren’t as successful, have created a functioning mechanism for large groups to work together.

"They’re able to mobilize communities to try to get projects done. In that sense, these Promise Zones, even without any money, could be effective to create a broker who brings the right people in to get things done,” Partridge said. “One needs a lot of patience. Quick-success solutions are just not effective. If it was so easy it would have been done.”

amcdonald@deseretnews.com

Twitter | @amymcdonald89

Promise Zones offer new hope to high poverty areas