IRVING, Texas (AP) — Imagine this: Deion Sanders high-steps across the stage at the Pro Football Hall of Fame induction ceremony, circling his newly unveiled bust. He looks at it quizzically, as if something’s missing. He then reaches for his back pocket, pulls out a do-rag, places it on the head of the statue and smiles.

Why not? Even today, long after the “Prime Time” of his career, Sanders is all about being flashy.

For 14 seasons, Sanders strutted his stuff across the NFL, a threat to score — or at least shake things up — on defense, special teams and occasionally offense. His talent was undeniable, although often overshadowed by his flamboyance.

His induction Saturday night will seal his greatness. Getting in the first time he was on the ballot is further confirmation he was among the most dominant players of the 1990s, arguably one of the most dynamic players of any era. He’s also one of the most unique, a trend-setter whose legacy is still evident every Sunday.

“Deion had the ability to not only focus on his craft and play football at the highest level, he could also entertain,” said Eugene Parker, Sanders’ agent and close friend who will present him for induction. “He always used to say, ‘I do what I love and I love what I do.’ He wanted to express that exuberance for what he was doing.”

The first time he returned a punt in the NFL, he took it 68 yards for a touchdown. He would score 22 touchdowns five different ways — 19 on defense and special teams, the most in NFL history. He returned two interceptions at least 90 yards for touchdowns in a single season, another first. He made the NFL’s all-decade team in the 1990s as both a cornerback and a punt returner.

But those are just lines on a resume. They don’t do justice to what kind of threat he was during his peak years. That was best evidenced by the feeling fans, foes and even teammates had every time a ball headed his way; everyone held their breath to see what he would do with it.

Sanders had the speed and moves to weave his way through traffic, into the open field. And that’s where the real show began.

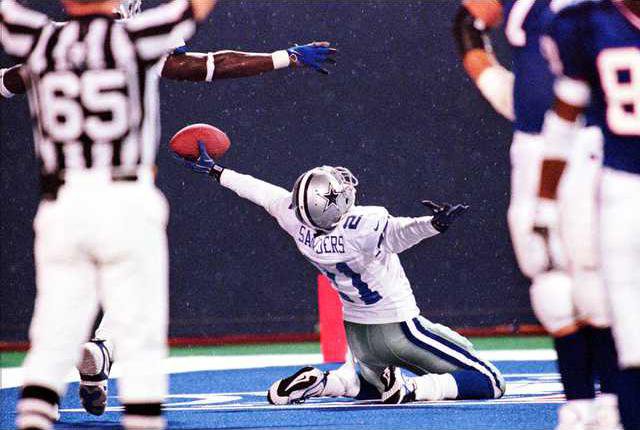

What previous generations considered taunting a beaten foe, Sanders considered performance art. Putting a ball behind his head or strutting or taking scissor-steps, he was always looking for fun ways to showcase himself. He wanted to be more than a great player, to be someone who all by himself was worth the price of admission. Love him or hate him, he often was.

“Deion did it all,” Parker said. “He would dream the impossible dream and then go out and make it happen. He wasn’t going to be limited or defined by someone else’s views.”

After establishing himself as an All-Pro with the Atlanta Falcons, Sanders wanted to show he was more than a great player on a mediocre team. So he went to the San Francisco 49ers to help them try ending Dallas’ two-year reign as Super Bowl champs. He was voted the NFL’s top defensive player of that season. The 49ers indeed won it all, knocking off the Cowboys in a classic NFC championship game, highlighted by Sanders’ stifling performance against Michael Irvin.

Then, to further prove what a difference-maker he was, Sanders switched sides, joining Irvin and the Cowboys the next year and helping them regain the throne as Super Bowl champs.

Two seasons, two teams, two titles. With a $12,999,999 signing bonus in between. Oh, one more thing — in his spare time, he played outfield in the major leagues and put out a rap album featuring songs such as “Y U NV Me” and “Must Be the Money.”

“He was the king,” Parker said. “At that time, you had Michael Jordan out there, but Deion was the hottest thing in sports because he was year-round. People would literally say, ‘What did Deion do today?’ Even the announcers got into it. He brought more enthusiasm and interest to sports.”

Jerry Jones was so shaken by the huge check he had to write to sign Sanders — nearly double the $7 million bonus he’d given Troy Aikman — that he flew to his childhood home for some soul-searching.

He flew back convinced it was a risk worth taking, in part because of the promotional dividends of having Sanders in a Cowboys uniform. Jones and Sanders even wound up co-starring in several television commercials. One was a knockoff of the TV soap opera “Dallas;” in another, Jones asks Sanders if he’ll play offense or defense, football or baseball, for $15 million or $20 million, and his answer every time is “Both!”

“What you see is ‘Prime Time,’” Jones said. “He knew that he certainly had a gift, and then he also has good instincts when it comes to being interesting. You say, ‘Wouldn’t that much talent and work ethic make you interesting?’ Deion understands that to some degree controversy can fuel that kind of interest. Deion’s flair was good for every team he played on — a big positive, not one negative. It was a very positive thing for all of his teams.”

Sanders played from 1989-2000, then from 2004-05. After Dallas, he spent a season in Washington and the comeback years with the Baltimore Ravens. He took a handoff in each of those last two years, a subtle reminder that he could still be a threat at ages 37 and 38, several years removed from his dual-sport career. (He played baseball from 1989-95, then again in ‘97 and 2001.)

“Deion was a fraud — a fraud, OK?” Jones said. “He wanted it to look easy, but he was a hard worker. He would give just enough at practice to be a team player in strength and conditioning, but when he went home he worked like a dog on his strength. He wanted everyone to think he was a natural. He was, but it wasn’t only because he was born like that. He worked.”

Sanders covered receivers so well that quarterbacks knew the odds were low of beating him. They also knew that if Sanders intercepted the pass, he might return it for a touchdown; even a 10-yard return could be dazzling enough to fire up the crowd and swing momentum. (He averaged 25.1 yards on his 53 career interceptions.) So quarterbacks learned to avoid him, tuning out whatever side of the secondary he roamed.

“If ‘shutdown cornerback’ didn’t start with him, he gave it credence,” Parker said.

Sanders also brought an offensive mindset to defense.

He wasn’t content with intercepting a pass or recovering a fumble. He wanted to score every time he got his hands on the ball. He made it look like so much fun that everyone started doing it. For better or worse, jumbo-sized linemen have gone away from the premise of securing a loose ball, instead trying to scoop up and running, or finding a swift teammate who might be able to pull off a Sanders-esque return, complete with some sort of celebration not just in the end zone, but along the way.

Another part of his legacy is all the defensive backs who wear No. 21. Many do so as a tribute to Sanders, much like Jordan popularizing 23 in basketball.

“Deion was ‘Prime Time,’ ‘Neon Deion,’ always that flashy player that everybody wanted to be,” said Mike Jenkins, the Cowboys cornerback who now wears 21. “He always stood out and he let it be known that he was one of the best. He definitely made it exotic to play cornerback.”

Although Jenkins’ jersey number honors the late Sean Taylor, Jenkins’ connection with Sanders runs deep: Jenkins’ uncle, Tracy Sanders, is Deion’s cousin and they were teammates at Florida State. So Deion Sanders has been a friend and mentor to Jenkins for as long as he’s been playing football. Just before every game, Jenkins watches highlights of Sanders “to have that mindset that I can shut down a whole side of the field.”

When he was elected to the Hall of Fame in February, Sanders said he never cared what others thought, but acknowledged how honored he felt. If nothing else, it helped justify the Hall of Fame gallery he’d already built in his monstrous home.

He also told this story that helps explain the motivation behind everything he’s accomplished: “Next to the Bible, my favorite book was ‘The Little Engine That Could.’ I read that story so many times, I know it by heart. ... A couple trains passed that engine until he started saying to himself, ‘I think I can. I think I can. I think I can.’ And that’s what I modeled my career after. I mean, it sounds arrogant, it sounds brash, it sounds cocky. But it was real.”

NEON DEION

Flamboyant Sanders finally reaches summit